Engineer of the Week No.77: Marjem or Marynia Chatterton (nee Znamirowska/Znamerovschi) BSc, FIStructE. (September 1916 – March 2010) 103 years since the month of her birth in Poland we remember structural engineer Marjem Chatterton, who was a real pioneer in the then newly-emerging nations of Israel and Zimbabwe, as well as an early female engineer in her field. Marjem Chatterton was the first female fellow of the Institution of Structural Engineers and designer of many of Zimbabwe’s first skyscrapers, including that nation’s national bank building. Born Marjem or Marynia Znamirowska in Warsaw, Poland, in September 1916, she grew up in a large Orthodox Jewish family, where girls’ education was considered important. She had planned to return to Poland to study chemical engineering at the University of Warsaw, but in 1934 it was clear that the situation for Poland’s Jews was worsening, so she enrolled at the Hebrew Technical Institute in Haifa. Known as the ‘Technion’, one of her aunts – Rachel Shalon, the first female engineer in the country – was a faculty assistant there. Photos of Marjem in class show that she was far from being the only woman studying engineering at the Technion. Graduating in civil engineering in 1939, with the first distinction in engineering awarded by the Technion, Znamirowska took a job that had been offered to her by a faculty member, Josef Edelman, who ran the Technical Office of the Collective Settlements Association, building some of the country’s largest kibbutzim as well as factories and bridges. She also assisted with paramilitary roles during the war. Although her own parents escaped from the Nazis, most of the rest of the family were lost in the Holocaust. In 1947 the war, Marjem and her British husband, Frank Chatterton, emigrated with their children to Southern Rhodesia, where she found a job as a reinforced concrete designer within 2 days of arriving in the country. Her experience with reinforced concrete structures in Palestine was particularly useful, as at that time it was nearly impossible to get hold of heavy steel sections locally. Southern Rhodesia was socially very conservative and everyone was taken aback to be working with a femal engineer but, once her competence became evident, her ‘oddity’ meant she was soon very well-known. Specialising in multi-storey structures, Initially she worked for Lysaght and Company but in 1969 she established her own consulting firm, M. Chatterton and Partners. As well as prestigious urban skyscrapers, she also designed many industrial facilities for the cotton, fertiliser, and sugar industries. In 1976, the worsening political situation in Zimbabwe led to her moving to Leeds University as a lecturer, and also became involved in the university’s campaign to encourage girls into engineering, giving careers talks in girls’ schools. In 1984 she returned to consultancy in Zimbabwe, also teaching at the national university. Zimbabwe’s independence in 1980 meant that sanctions were lifted and investment poured in and she gained a lot of work and her buildings still define the skyline of Zimbabwe’s capital Harare, with her last major project – the 26-storey Reserve Bank – being the tallest office building in the country. By 1999, although Marjem was still working (at the age of 83), the political situation was again worsening and she decided to take retirement and return to the UK.

1 Comment

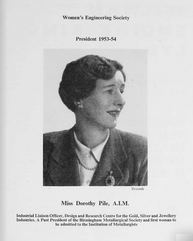

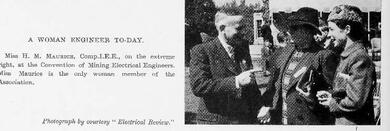

Engineer of the week No.76: Mrs. Ayyalasomayajula Lalitha BEng, MIEE (27 August 1919-12 October 1979) On the centenary of her birth we remember India’s first female electrical engineering professional. Mrs. Ayyalasomayajula Lalitha was India’s first female to become a professional engineer. Born in Chennai (formerly Madras) in 1919, she would follow her father, Pappu Subba Rao, into his profession of electrical engineering. She was fortunate to have such a father, since she found herself as a widow with a daughter at the age of only 22 and he supported her wish to complete her secondary education and go to study engineering at the College of Engineering, Guindy (CEG) where he was a professor. This was against all traditions of what widows should do and of course was a totally unique choice of career for an Indian woman at that time, although 2 other women did join the college to study civil engineering while she was there. Lalitha graduated in electrical engineering in 1943, but there was a further, final, requirement for the degree: practical training. Lalitha completed her one year apprenticeship in Jamalpur Railway Workshop, which was a major repair and overhaul facility. She then took her first job: as an assistant engineer at the Central Standards Organization of India, in Simla. This enabled her to live with her brother’s family who helped by looking after her young daughter. In 1946 she went to work for her father, assisting him with his research and patents but in 1948 made her final move, to the company for which she would work for the rest of her career: Associated Electrical Industries (AEI). With AEI she became a design engineer specialising in power transmission equipment, including protective gear, substation and generator design. The most significant contract on which she worked was theBhakra Nangal Dam, but she then worked more on contract engineering, as an intermediary between the equipment manufacturers in England and the local installation and servicing engineers, which often required field visits. She continued to work in the same office of AEI, in Kolkota (Calcutta) later taken over by General Electric Company (GEC). In 1953 the Council of the Institution of Electrical Engineers (IEE), London elected her to be an associate member, promoted to full member in 1966. She retired after a 30 year career and died in 1979.  Engineer of the Week No. 75: Kathleen Mary Cook (Mrs D.I.H. Goodwin) AMIMechE, FIBF MIProdEng (25th August 1910 - 1971) On her 109th birthday we remember Kathleen Cook mechanical engineer, entrepreneur and WES President. Kathleen Cook was born in London in 1910 and educated at La Convent of the Sainte Union des Sacres Coeurs, North London, followed by a 7 year apprenticeship in 1928 at Hercules Engineering Company, in North London. As far as we can tell she had no formal post-school technical education. Her father, initially a machine shop foreman in the automobile industry, became a director of this small general engineering and press tool company. During the Second World War she and her three brothers ran a factory in Northolt, making gun breech mechanisms. In her spare time she liked to volunteer as a mechanic at Brooklands race track. In 1942 she was appointed director of Hercules Aircraft Construction Co Ltd and in 1945 was a founder member of Universal Equipment Co Ltd. In 1949 she set up Kainder Ltd, to make her own invention, the Kainder Mobile Bed. In 1951 she joined Wilman Engineering Co Ltd, a small manufacturer of making electronic equipment and automatic control units, which was struggling financially and helped rescue it. She remarked that the very hard times in engineering she experienced during the depression when she was just starting her career, stood her in good stead when she took on and turned around various struggling firms in her later career. She married Dennis Goodwin, at this period, who was a director of Brentford Foundries, and George Spicer Ltd. She was a fellow of the Institute of Production Engineering and of the Institution of British Foundrymen (their first female fellow). She died in 1971 after a long illness. Kathleen joined the Women’s Engineering Society in 1931 and was immediately energetically involved, joining the council in 1936, vice president in 1951 and president in 1955-6. She died in 1971 after a long illness.  Engineer of the Week No.74: Phoebe Sarah Hertha Ayrton (nee Marks) BSc, MIEE (28 April 1854 – 26 August 1923) 96 years ago this week we lost one of the first British women to contribute to engineering and sciences, Hertha Ayrton. Hertha Ayrton, engineer, physicist, mathematician and inventor, was a pioneer in the application of science to practical engineering problems and was one of the first women to work in electrical engineering in the UK. Ayrton, born Phoebe Sarah Marks, received an usually excellent education for her time. Her mother, a widowed seamstress, thought that girls needed a good education because they would have harder lives than boys. She studied with an aunt who ran a school in London, and then attended Girton College, Cambridge to read mathematics. Known to her family as Sarah, she changed her name to Hertha, inspired by a Swinburne poem. After passing the examinations (she wasn’t awarded a degree as Cambridge didn’t give degrees to women at this time), Hertha returned to London to teach. She was awarded a BSc degree from the University of London and took out patents on a line divider, one of numerous inventions she would patent in her lifetime. Hertha also attended classes at Finsbury Technical College, where she met her future husband William Ayrton.  Engineer of the Week No. 73: Mrs May Maple (nee Newby) (8th Aug 1914- 19th August 2012) FIEE, CEng., FRSCA On the seventh anniversary of her death, we remember electrical power engineer and WES president, May Maple. Mrs May Maple’s life before she joined the Women’s Engineering Society in 1950 is unclear, but she is likely to have been born in 1914 in Gateshead to Mr & Mrs Albert Newby, and to have married Wiliam Maple in 1939. She started her engineering career as a purchasing officer with the London Transport Board and then moved to Edmundson’s Electricity Corporation. She gained an HNC in Electrical engineering doing a 5-year nightschool course from Action Technical College, whilst at Edmundson’s. In 1948 when the electricity supply industry was nationalised she continued her work in the Contracts department of the British Electricity Authority, gradually being promoted until she was a2nd Assistant engineer in Contracts Department (1953). In 1955 she gained her associateship of the IEE, rising through its membership grades as MIEE and Chartered Engineer (1966), to become an FIEE in 1969. By 1965 she was a Contracts Officer with the CEGB, responsible for all electrical equipment contracts and only woman in this position. She was active in the Women’s Engineering Society from not long after she joined, initially on the committee of the London branch,getting involved in education outreach to schools and taking on the onerous task of finding paid advertising for The Woman Engineer for over 10 years. In 1970-71 she was the Society’s president and also actively supporting the International Conferences of Women Engineers and Scientists. This involved travelling widely which she continued into her later years. She was made an Honorary Member of WES in 1979 and awarded the society’s highest award, the Isabel Hardwich brooch, in 1991. She died in 2012 and left a legacy to the society in her will.  Engineer of the Week No.72: Caroline Harriet Haslett DBE, JP, Companion IEE (17 August 1895 – 4 January 1957) Today on her 124th birthday we remember Caroline Haslett, engineer, founding Secretary and President of the Women’s Engineering Society. Dame Caroline Haslett was arguably the woman who had the most impact on the founding and continued success of the Women’s Engineering Society. Born in Sussex in 1895, her father Robert Haslett was a railway fitter. This perhaps explains why, on leaving school and getting a very junior clerical job with the Cochran Boiler Company in Annan, Scotland, she was so dissatisfied with the job that she asked if she could move to the shopfloor and learn the technical side. In 1918, she answered an advertisement for a ‘Lady with some experience in engineering works as organizing secretary for a women's engineering society.’This was the Women’s Engineering Society, and she would go on to be the guiding influence of the Society, editing the Journal and becoming President in 1941. She also co-founded the Electrical Association for Women, an organisation formed to reduce the drudgery of women’s everyday lives by encouraging the use of electricity in the home. She edited its journal, the Electrical Age, for 30 years and the 6 editions of Electrical Handbook for Women. When she retired from the EAW the association had 14,000 members, most of them housewives, domestic science teachers, and educationists, organized in 160 branches. It flourished into the 1980s and many women remember their mothers attending its courses, evidenced by one of the distinctive explanatory tea towels.  Engineer of the Week No.71: Professor Margaret Law MBE BSc CEng FIFireE FSFPE (1928 - 27 Aug 2017) Just two years since her death we remember fire safety engineer, Margaret Law. Margaret Law was considered by her contemporaries to be a pioneer in the, then new, field of fire engineering. Born and educated in London, she gained her degree in maths and physics from the University of London and got her first job in 1952, at the government’s Fire Research Station in Borehamwood, only 3 years after it was established. Her experimental work featured on the FRS’s research report cover in 1952. During her 20 year association with the FRS (which later became part of the Building Research Establishment) she contributed to 34 Fire Research Notes (reports). The topics ranged from the small, domestic issues of cooker fires in caravans and prefabs, to the Cold War concerns of the potential for nuclear radiation to start fires: “On The Possibility Of Ignition Of Materials By Radiation From Nuclear Explosions”. Her interests were in the effects of materials and structures on fires and how they spread, such as how fire moves through high rise flats with balconies, or the optimum protective coating for structural steelwork.  Engineer of the Week No. 70: Johanna Weber Dr. Rer. Nat. (8 August 1910 – 24 October 2014) On her 109th birthday we remember aerodynamic engineer Johanna Weber. Dr Johanna Weber, was one of the foremost aerodynamicists of her generation and contributed significantly to the design of the Concorde and other supersonic swept-wing aircraft. Born in Düsseldorf, Germany she lost her father in the First World War, making her eligible for financial support, so she could attend a convent school and then go on to university. She graduated Dr. rer. nat. (a first degree but to doctoral level, in natural philosophy or physics) with first-class honours in 1935. Despite teacher training her refusal to join the Nazi Party excluded her from such work but, rather oddly, not from work in armaments. She first worked for the massive Krupp company in Essen as a researcher in ballistics doing mathematical computations using mechanical calculators. In 1939 she moved to Göttingen’s Aerodynamics Research Institute (Aerodynamische Versuchsanstalt Göttingen) to begin a lifelong collaboration with Dietrich Küchemann on aerodynamics which, amongst a mass of other significant publications, led to their seminal book,Aerodynamics of Propulsion. At the end of the War, senior people from the Royal Aircraft Establishment Farnborough were sent to Germany under Operation Surgeon to survey German aeronautical resources and research. In addition to acquiring many wind tunnels, they also recruited Küchemann and persuaded Weber, probably on the recommendation of Hilda Lyon who was part of the RAE team sent to Germany wrote the report covering their work. They arrived in 1946 and until 1953 were ‘enemy aliens’, on repeat 6-month contracts, until they then were naturalised as UK citizens. From then on Weber lived with the Küchemann family until eventually she bought the house next to theirs. Her initial work at RAE was in Frances Bradfield’s Low Speed Wind Tunnels division, on air intake cowlings for jet engines, on which she co-authored a series of papers. The work for which she is more remembered today was on wing design, for which she showed that a thin delta wing could generate sufficient lift to for take-off and landing for supersonic planes, and was implemented in the iconic Concordes. Her design work was also involved in wing shape for both the VC10 airliner and the more recent Airbus A300B. She retired from the RAE in 1975 at the grade of Senior Principal Scientific Officer, but still did some consultancy with them for a while, whilst also pursuing personal interests in geology and psychology. She never married and helped financially support members of her family who remained in Germany. For a more detailed technical review of her work, see John Green’s obituary for the Royal Aeronautical Society: https://www.aerosociety.com/news/obituary-dr-johanna-weber/ Engineer of the week No.69: Elizabeth Jane Smith (3 October 1889-?)

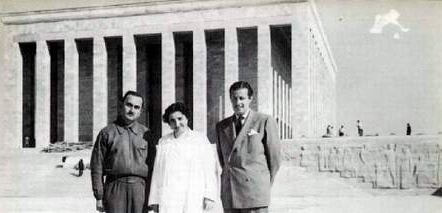

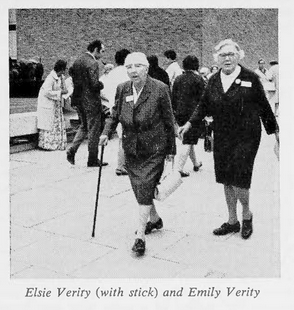

Today we remember Elizabeth Smith, the first woman to study engineering in a Scottish University. Elizabeth Smith was the first woman to study engineering in Scotland. Her family background is a bit unclear but her mother may have been a single parent as they lived with her mother’s parents and siblings and there is no mention of a father in the household. Her grandfather was a forester and lived in the Forester’s Cottage in Currie, Midlothian. Elizabeth’s first school was Currie primary, then James Gillespie’s for 4 years from the age of 12, and finally the Broughton Junior Student Centrewhich was a kind of college bridging school to university.At the centre she gained passes in English, Mathematics (Higher), Latin, Dynamics, French, and Italian, sufficient to take her to university. She started her studies at the University of Edinburgh, at age of 20, in the academic year 1909-10, initially on an Arts degree.She then changed course to pursue a Pure Science degree in the Faculty of Science for the following three academic years. As she came from a very humble household, her mother working as a low-paid shop assistant, it is not clear how her education was funded, probably by various scholarships but neither her schools nor the university have any records on this matter.  Engineer of the Week No.68: Gladys Lawson (13th July 1904-September 1998) Today we remember Gladys Lawson, one of the unsung heroes of the engineering world: a draughtswoman who designed and drew power transformers. When seeking the stories of women in engineering, we are mostly invited to admire the ‘stars’ of the profession: women who rose to run companies or research departments, women who innovated or patented, women who campaign for the profession. It is as well perhaps to remember that few of us ever rise to such heights, most engineers (of any gender) do not become company managers or take out patents but still enable our technological society to function and the world to go round. For those of our fore-sister who were destined never to be ‘Straight-A’ (or even modest B) students, there is still a role model to offer to today’s girls and young women: there are still excellent careers for you in engineering, even (especially?) if you never get an engineering degree but become a good, reliable technician. With this in mind here is someone of that sort: a woman who came from the humblest background with little education but rose to responsibility in a major engineering firm’s drawing offices. Lancashire lass Gladys Lawson was born in 1904 into a modest working class family, in which her father was a clerk for the local tram company. She left school at 15 and joined the massive Metropolitan Vickers engineering company in Manchester on its staff. She herself said she was certainly no ‘engineering prdigy’ but was hoping to take commercial training to improve her clerical skills and rise to a secretarial grade. This she achieved and became the secretary to the Chief Engineer of the Transformer Department. At some time in the1920s she fell ill and was out of work for several years. On her return in 1929 she felt unsettled and was delighted to make a change when a vacancy for a Drawing Office Assistant came up.  Engineer of the Week No.67: Elsie Eleanor Verity, FIMT/FIMI (14th August 1894 - April 1971) Today we remember “The First Lady of the motor trade”, Miss Elsie Eleanor Verity of Manchester. Elsie Verity, to become famed as “The First Lady of the motor trade”, was born in Barton upon Irwell, Lancashire, in 1894, to William and Lilly Verity, but lived almost her entire life in Manchester. Her father’s family had been in the metal trades for generations and he started out as a whitesmith, then a fitter and finally set up in his own business building bicycles and then running a motor garage. Her education was at Manchester’s Central High School and entered her father’s cycle-making and motor garage business at the age of 16. In this she was the beneficiary of a father who was happy to teach her all about his engineering skills and taught her to drive when she was only 13 years old, and a mere year later she was actually teaching others to drive. Initially she was the firm’s bookkeeper and typist, but she took courses at the Manchester College of Technology and Manchester High School of Commerce and gained a good deal of automobile engineering knowledge because when the First World War broke out she became a driving instructor for the armed forces and also for the Ministry of Pensions’ driving scheme for shell-shocked service men. She commented later that, even at the young age of 16, wartime pressures sometimes meant she was teaching girls even younger than herself how to drive.  Engineer of the Week No.66: Dorothy Lilian Pile FRSA, MISI, HonFISMe, HonFSLAET, HonMIM, FIMF, HonFIMet. (26th July 1902 - 1st February 1993) On her 117th birthday we remember metallurgical engineer, Dorothy Pile. Born in 1902 in Yorkshire, her father was a noted metallurgist, and Dorothy followed him into this field. She does not seem to have had any post-school education but went straight to work at the Midland Laboratory Guild at the age of 18 as a laboratory assistant and presumably learned on the job.The guild was established in 1918 as a co-operative organization providing testing services for several independent firms making non-ferrous products. She progressed there to become a technical assistant working with the scientist in charge, Mr R. Johnston. When he died in 1944 she became the Assistant Secretary of the Sheet Metal Industries Association. Throughout this time she had gradually become well known in metallurgy due to her research interests in the finishing of fine metalwork and jewelry and research on strain, corrosion cracking and surface defects. This led to her becoming an Associate of the new Institution of Metallurgy in 1947 and in 1949 she was elected at the Birmingham Metallurgical Society’s first female president. She was awarded fellowships in a number of metals institutions and returned the compliment in many cases by donated trophies in her name, for student competitions in the trade. In 1950, Dorothy was the only woman member at the Iron and Steel Institute’s annual dinner and therefore allowed to bring a female guest, which none of the male members were permitted - she brought Dorothy Cridland. In 1948 she moved again, to become the Industrial liaison officer with the Design and Research Centre of the Gold, Silver and jewelry trade, London. In 1983 she became the first female Honorary fellow of the Institution of Metallurgists and was presented with an inscribed silver dish. In 1966 she was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts and took an active role, contributing to discussions about involving younger people in the society. Having been involved in the Women’s Engineering Society since the 1940s, she became President in 1954 and donated our beautiful President’s Badge in 1964. She was freeman of the City of London and a member of the Goldsmith’s Company, and died in 1993, whilst living in the Goldsmiths’ Company’s almshouses in East Acton.  Engineer of the Week No. 65: Ruth Pirret BSc, MIM (24th July 1874-19th June 1939) On her 145th birthday we remember metallurgist and corrosion specialist, Scotswoman Ruth Pirret. Ruth Pirret was the first woman to graduate with a BSc in pure science from the University of Glasgow, in 1898, having been amongst the first women to be allowed to enter the university. Although her work was principally in chemistry, she can be considered to be included amongst the early women working in engineering due to her important contribution to the understanding of corrosion in marine boilers. Ruth was born in Kelvinside, Glasgow’s prosperous West End, while her father was minister at the United Free Church in Garnethill. The penultimate child in a large family, there must nevertheless have been sufficient resources to ensure most of them got excellent educations, since two of her older sisters set up their own nursery school and her younger sister, Mary, became a medical doctor, in addition to Ruth’s own university education. Having won various prizes and taken honours courses in Mathematics, Chemistry and Physiology, Ruth’s degree initially took her into teaching, then one of the few paid careers open to female graduates. In 1900-01 she was science mistress at Greenock High School and she is then thought to have taught in various other schools, possibly in Kilmacolm, Newcastle and Arbroath, before returning to the University of Glasgow in 1909 to undertake postgraduate research with Frederick Soddy. Soddy’s previous research assistant had been Winifred Moller Beilby, but she retired after their marriage in 1908 and Ruth Pirret took her place as his assistant. Their work was developing the disintegration theory of radioactivity and was published in two co-authored papers (in 1910 and 1911) on “The ratio between uranium and radium in minerals, which led to Soddy becoming an FRS and a professorship at the University of Aberdeen in 1914.During the First World War she became a Vice-Warden of Ashburne House Hall, a residence for female students in Manchester, where students remembered her for the morale-boosting activities she set up there.  Engineer of the Week No.64: Rosina “Rose” Winslade OBE (22nd July 1919 - 16th December 1982) MIMC, MASEE, FITE, AMBIM, MSIT Today, on the centenary of her birth, we remember Rose Winslade, accoustic and electronics engineer and technical educator. Rosina Winslade was another woman who became a highly respected professional engineer (and President of the Women’s Engineering Society) despite having had almost no formal education. Born in London in 1919 into a working class family, her father having various labouring jobs, she had to leave school at the age of 14 to work in a factory. Her own interest, and presumably demonstrable intelligence, led to her being moved to be a junior assistant in the laboratories. She started to take City and Guilds courses in Telecommunications Technology but was not able to finish due to a serious illness for 2 years. However by 1939 she was sufficiently knowledgeable and experienced to get a job with the Plessey Company working on development and production liaison on airborne equipment and direction finders. In 1947 she moved to become an engineer in the accoustics laboratory of Goodmans Industries Ltd, a company specialising in audio equipment, then (1950) joining Phillips Electrical Ltd as a sales engineer on electromechanical devices and instrumentation. That division became a separate company, Research and Control Instruments Ltd, with whom she worked until 1967, rising to become Manager (Technical) of their Electronics Division, mainly working on automation schemes. In 1967 she took a change of direction into technical education, which was to be a principal interest for the rest of her life, by become the Assistant Secretary of the Council of Engineering Institutions. This led to involvement in overseas educational organisations, in Europe and the Commonwealth and an appointment to the board of governors of University College Nairobi. She retired in 1977. Rosina was involved in many professional bodies, often becoming one of their first female members. She was an early member of Society of Environmental Engineers, perhaps due to her interest in vibration measurement, on which she published papers in the 1950s. Rosina was active in the Women’s Engineering Society from her joining in 1947 until just before her death. She gave talks, wrote articles, was on the council and became the Society’s President in 1966-67. In the Society’s 50th anniversary year, 1969, she was awarded the OBE for her services to the society, which continued until just before her death in 1982.  Engineer of the Week No.63: Eleanor Lettice Curtis (1 February 1915-21 July 2014) On the 5th anniversary of her death, we remember Lettice Curtis, pioneering commercial pilot and aeronautical engineer. Lettice Curtis was almost unique in being a pre-WW2 pilot who served through WW2 in the Air Transport Auxiliary and then carved out a full post-war career in the technical side of flying. Eleanor Lettice Curtis was born in Devon into a prosperous and well-connected family, her father W S Curtis being a barrister. She was educated at the very exclusive Benenden School for Girls and then read mathematics at St Hilda’s College, Oxford. In 1937 she gained her private pilot’s A certificate, at Yapton Flying Club, Ford, near Chichester, and a year later got the commercial pilot’s B licence, which enabled her to get her first flying job with C.L. Air Services in Eastleigh. Charles Lloyd was under contract to the Ordnance Survey, to take aerial photographs for mapping.In 1939 she went to work for the Ordnance Survey’s research department, drawing maps from aerial photographs and the following year joined her many flying friends in the Air Transport Auxiliary, initially at its Hamble base. During her war service, Lettice became the first female to fly the heavy four-engine bombers, including Halifaxes, Lancasters and the the US B-17 Flying Fortress. She had flown 400 of them by the close of the war.  Engineer of the Week No.62: Diana Joan Lavender MBE, CEng, MIMechE (21st July 1928- 13th March 2008) Today, on what would have been her 91st birthday, we remember Joan Lavender, defence electronics engineer and CAD pioneer. Joan Lavender was one of a generation of women engineers who managed to benefit from the post-WW2 demand for technical talent as the Cold War heated up. Born in 1928 into humble circumstances in Wolverhampton she seems to have been raised by her mother and grandparents. Her time at St Jude’s, the local primary school, revealed her as very bright and she won a scholarship to go to Wolverhampton Girls High School during the war years. She left school at 16 with credits in her school certificate exams and went to the local technical college to study to become a draughtswoman and engineer, coming out top in her year which gained her the student of the year award. In 1944 she started a 3-year apprenticeship at Waddington Tools Ltd. She then got her first job, as a jig and tool draughtswoman at Villiers Engineering Co Ltd1, Wolverhampton which she combined with more college studies, leading her to 2 years toolroom training experienceon special purpose machines. In 1948 she moved south to work for De Havillands (later became Hawker Siddeley and then British Aerospace), and also joined theInstitution of Mechanical Engineers, rising in its grades until she became a chartered engineer in 1956. As her work was in the defence industry, it was all top secret and it is difficult to know exactly what she worked on but we do know that her IMechE application showed that her specialisation then was production methods using early versions of programmable machine tools and she rose to become British Aerospace’s Computer Aided Design and Manufacture Controller, Air Weapons Division.Photos from her own album indicate that she worked on both the Blue Streak rockets and the Excalibur guided artillery shell. She was awarded the MBE for services to engineering,just before she retired in 1987.At her retirement party colleagues gave her a huge cartoon of her jealously guarding ‘her terminals’ (early computers). Joan never married and lived with her mother until the latter died in 1971. Her leisure interests were all focussed on the dog world, setting up the De Havilland Dog Training Club for work colleagues. This later became the Hatfield South Dog Training Club, which is still flourishing under the leadership of those she trained in their youth and where she remains warmly remembered. Engineer of the Week No. 61: Ray Strachey (nee Rachel Pearsall Conn Costelloe) (4th June 1887 - 16th July 1940)

On the 79th anniversary of her death, we remember Ray Strachey, who started out to be an engineer but spent most of her life campaigning for women’s rights. Ray Strachey, born Rachel Pearsall Conn Costelloe (4 June 1887 London – 16 July 1940) is best known as a politician and writer. However she had a strong interest in engineering and was planning to study it before she was diverted by her marriage to Oliver Strachey in 1911. Ray studied mathematics at Newnham College, Cambridge. During her studies she became involved with the campaign for women’s suffrage through her friendship with Philippa Strachey. Ray joined what became known as the Mud March in February 1907, and addressed meetings during summer 1907. She took part in the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies caravan tour in July 1908. [Text by guest EOTW author, Katherine Kirk]  Engineer of the Week No.60: Letitia Chitty M.A., C.Eng,. F.R.Ae.S., M.I.C.E. (15 July 1897-29 September 1982) On her 142nd birthday we remember Letitia Chitty, aeronautical and civil engineer. Letitia Chitty was a talented mathematician who translated that into engineering, analysing the stresses of airframes, ships and civil engineering structures and became the first female fellow of the Royal Aeronautical Society. Born into a well-off family in London, her father was a barrister, Letitia’s godmother was Violet Jex-Blake, niece of Sophia Jex-blake, the first female medical graduate in the UK. Her mother’s male relatives were part of the public-school heirarchy and it is clear that Letitia had support for her educational aspirations.She attended Kensington High school and then started to study maths at Newnham College, Cambridge. However, having done Part I of the Mathematics Tripos, she left to go to the Admiralty Air Department in 1918, where she worked with a group of other young women and men under Alfred Pippard. She recalled of this period: “There were no programmes, no calculating machines … we relied upon our slide rules and arithmetic in the margins … Lives were at stake and we couldn’t afford to let anything go through wrong.”  Engineer of the Week No. 59: Hilary Jeanette Kahn (Mrs Napper) BA, PGDipl (11th July 1943 - 4th November 2007) On her 76th birthday we remember Hilary Kahn, pioneering software engineer who laid the basis for CAD for engineers of today. Hilary Kahn was a software engineer, a career she arrived at almost by accident. Born in Cape Town, South Africa, in 1960 she left to get away from the apartheid politics of that era and, with her mother’s support, came to the UK, where she spent a year getting the A-levels she needed to go to university. She went to Bedford College University of London and graduated with a classics degree in Latin and Greek in 1964, with the idea of becoming an archaeologist. Not being able to find a job she happened to see an advert for computing postgraduate course at University of Newcastle and with no real idea of what it might be, applied thinking it looked interesting. Due to her lack of maths she was put into the Diploma in Business Processing, where she learnt COBOL (and Algol from a book), whilst also being one of the students who ran the university’s computing service in the evenings. The university’s computer was a KDF 9 machine from English Electric, descended from their earlier DEUCE machines (see Winifred Hackett’s involvement with those). Her diploma was supported by funding from English Electric in Kidsgrove, in return for which she had to work for them for a year after her graduation in 1965.  Engineer of the Week No.58: Elsie Joy Muntz (Mrs Davidson) (14 March 1910- 8 July 1940) Today, on the 79th anniversary of her untimely death, we remember Joy Muntz, pioneering engineer-pilot. Joy Muntz, as she was generally known, was a pioneering commercial pilot and aeronautical engineer. Born in 1910 in Ontario, Canada, she lived mainly in England. Her father, Rupert Gustavus Muntz was a clerk who died when she was only 4 years old. Little is known of her early life and education but in 1928 she (and her sister Hope) got jobs as ‘fabric hands’ at De Havillands’ factory where they would have been fitting fabric to the wooden frames of wings and fuselages but luckily for them they did not do the application of the toxic doping varnishes. Joy tried to get work in the drawing office but was turned down. However she did manage to get a minor job in the engineering workshops – stamping numbers on parts – which gave her the chance to apply for a trade apprenticeship (at 6d an hour, the equivalent of 2.5p!) in the engines department. Initially, she was set to cleaning out sumps, followed by the dismantling, cleaning and reassembling of new engines prior to their tests. So she soon knew every part of an aero-engine and started to take flying lessons in her lunch breaks. However that winter she crashed her motorbike, breaking her leg, which put her out of work until October 1929. De Havillands did take her back and set her onto brake testing but the firm’s flying school was about to move to Stag Lane and when she asked to go with it, she was turned down because she was not a ‘premium’ apprentice (ie paying for her training).  Engineer of the Week No. 57: The Rt Hon. Mary Parsons, Countess of Rosse (née Field) (1813-22 July 1885) Today we remember Mary Parsons, blacksmith, photographer and ancestor of the founders of the Women’s Engineering Society. Yorkshirewoman Mary Field was born into a wealthy family of landowners, the Fields of Heaton Hall, and her privileged upbringing gave her an exceptional mathematics education rarely available to girls in the early 19th century. At the age of 23 she married William Parson, Lord Oxmantown who soon inherited his father’s title becoming 3rd Earl of Rosse, so that Mary became Countess of Rosse. Although William was a good deal older than Mary they were well-matched as they had many technical interests in common. William was interested in astronomy and Mary helped him to build an enormous telescope, known as the ‘Leviathan of Parsontown’. Most unusually for any woman of that time, and especially for a woman of her class, Mary is said to have had expert blacksmithing skills and made the framework which supported this gigantic instrument. She also made an elaborately decorated iron keep gate for their estate,using the lost-wax method and the estate’s peat-fuelled furnaces.The couple were what we would now call ‘early adopters’ of new technologies and their next activity was photography. Again, Mary started taking and developing her own photographs, using the waxed-paper negative method, including some of the telescope. In 1854 these were exhibited at the Photographic Society's first show in London, earning her the Photographic Society of Ireland's first ever Silver Medal. Although only 4 of her 11 children survived to adulthood, one of them was Sir Charles Parsons who, with his wife Katharine and daughter Rachel, were the principal instigators and supporters in establishing the Women’s Engineering Society in 1919.  Engineer of the Week No.56: Elizabeth Helen MacLeod Georgeson (July 1895-?) In the month of her 124th birthday, we remember Elizabeth Georgeson, Scotland’s first female engineering graduate. Elizabeth Helen MacLeod Georgeson is believed to have been the first female engineering graduate from any Scottish university. Born in the West End of Glasgow where her father, Frederick Hugh Georgeson, was a Minister of the United Free Church, the family later moved to Edinburgh where she had her secondary education at Canaan Park College. She started studying engineering at the University of Edinburgh in 1916 when she was 21, at the height of World War 1, when many women of all social classes were taking on new roles, often in engineering fields previously barred to them. Elizabeth studied chemistry, maths, introductory engineering and natural philosophy (1st year); technical maths II, junior engineering labs and junior engineering drawing (2nd year); and heat engineering, junior engineering fieldwork, applied maths, senior engineering labs, senior engineering fieldwork, geology and senior engineering drawing (final year). She graduated with BSc in engineering in July 1919 and also gained a 1st class certificate of merit in mechanical engineering and 2nd class certificates in junior engineering labs and engineering fieldwork. On graduating she became an articled pupil to a surveyor, with a view to qualifying as a Civil Engineer. The only image we have of her is from a 1934 group photo of the Edinburgh Mathematical Society, so she was presumably a member. She was also a member of the Women’s Engineering Society in 1920, the year after its formation, when they published her article on “The magic of mathematics”. She worked for the Safety in Mines Research Laboratory in Sheffield, from which she co-authored 7 papers based on her research work done there between 1926-42.Her first publication was in 1925, about the properties of cement particles, but the majority of her papers were on the properties and behaviour of gases in mines. In 1942 she won the only senior scholarship that year from the Sir James Caird's Travelling Scholarships Trust, giving her £280 to travel to study aeronautical engineering. Presumably she could only have travelled within the UK, given the war situation. She also wrote poetry and her poem, Flotsam, a contemplation on old age, was published in 1952 in a selection of short poems from the Festival of Britain.  Helen Monica Maurice(Mrs Jackson) OBE (30 June 1908 – 20 September 1995) On her 111th birthday we remember Monica Maurice, lighting engineer. If Florence Nightingale was known as the “Lady with the lamp” to the soldiers of the Crimean war, Monica Maurice was well-known in Yorkshire as the “Lady of the lamp” to that county’s coal miners. Helen Monica Maurice was born in the industrial Midlands of England in 1908. Her father William Maurice’s Wolf Safety Lamp Company made safety lamps for mining and quarrying, having bought the rights to a German design. She had an excellent education, first at Bedales school where she was head girl, and then at the Sorbonne and Hamburg universities, followed by commercial training. She emerged with excellent language and secretarial skills which she put to use assisting her father. Although she was not initially trained as an engineer, it soon became apparent that she was acquiring a technical appreciation of the company’s work and was sent for about a year’s training at Friemann and Wolf factory, from which her father’s firm had the UK rights. She trained in the drawing office, laboratory, machine shops and foundry as well as visiting other industrial sites in Germany at a time when the Nazis were coming to power.  Engineer of the Wek No.54: Sabiha Rifat Gürayman, BSc (1910 – 4 January 2003) Today we remember Turkey’s first woman engineer, Sabiha Rifat Gürayman. Sabiha Rifat Gürayman was Turkey’s first female construction engineer and saw her career as a way to repay a ‘debt’ to Kemal Atatürk, whose revolution in the early 20th century paved the way to modernity for Turkish women. To this day, Turkey has one of the highest percentages of women engineers in the world, due in large part to this revolutionary zeal to modernise the nation in the 20th Century. Born in 1910 in Manastir, in what was the far west of the Ottoman empire, now part of Albania, she was the daughter of a soldier. Her education was at girls’ high schools in Istanbul and then in 1927 she and Melek Erbul became the first female engineering students at the Higher Engineer's School (now Istanbul Technical University). The students and staff took some while to become accustomed to female students as the school had, until the year before she started, been a military school. During her student years she also took up volleyball, playing with and then captaining the men’s Fenerbahçe volleyball team, leading them to become Istanbul champions in 1929. She graduated in 1933 and her first job was with the Ankara Public Works Directorate, and then the Ministry of Public Works. She worked on designs for schools and other public buildings and in 1935 oversaw the construction of the Kemer Bridge at Beypazarı Village, west of Ankara. This project required her to camp and work in the field, and even wear trousers, which would have been highly remarkable to the rural residents. The startled villagers were so delighted with their new bridge that they renamed it the “Girls’ Bridge”, to honour Sabiha’s work. She was appointed Chief Construction Engineer in the Ministry of Public Works and undertook her most significant work on the 10-year project to build the Anıtkabir Hürriyet Tower, which is the mausauleum of Turkey’s founding father, Mustafa Kemal Attaturk. Her portrait is displayed in the tower to commemorate her work. She retired in 1963 and her husband died in 1993. Due to her own childhood as the daughter of a soldier, she left all her wealth to the Istanbul Technical University Foundation and Fevzi Akkaya Basic Education Foundation, to provide scholarships to the children of soldiers who died in their nation’s service.  Engineer of the Week No.53: Verena Holmes B.Sc. (Eng.), AMIMechE, AIMarE. MILocEng (23 June 1889 – 20 February 1964) On her 120th birthday and the 100th anniversary of the Society she founded, today we remember Verena Holmes, practical mechanical engineer, patent holder and entrepreneur. Verena Holmes was the Women’s Engineering Society’s first practicing engineering president, who had a life’s career in the field. Verena Holmes was born in 1889 in Kent, where her father Edmund Holmes was a schools inspector and author. She attended Oxford High School for Girls and after initially working as a society photographer found her true vocation when the First World War opened the door to engineering. Her first job was building wooden propellers at the Integral Propeller Co., Hendon, whilst attending evening classes at Shoreditch Technical Institute. She then worked at Ruston and Hornsby, an aero engine firm in Lincoln, as their Lady Superintendant responsible for the selection, control and welfare of 1,500 female employees. However, her real interest was engineering and she persuaded the directors of the company to let her start as an apprentice in the fitting shops. Holmes gained experience as a turner and completed an apprenticeship as a draughtsman before the end of the war. In 1919 she was the only woman who was allowed to stay on with the firm. She attended Loughborough Technical College, and gained a BSc (Engineering) degree extramurally from London University in 1922. From then onwards Verena would produce a steady stream of inventions, of which 17 were patented. One of the more significant was the Holmes-Wingfield pneumo-thorax apparatus, which she designed and made for for Dr RC Wingfield, for his work at Brompton Hospital tuberculosis sanatorium. |

- Home

- Electric Dreams

- All Electric House, Bristol

- Top 100 Women

- Engineer of the Week

- The Women

- Timeline

- WES History

- EAW

- Teatowels For Sale

- 50 Women in Engineering

- Museum Trails

- Waterloo Bridge

- History Links

- Blue Plaques

- Virtual Blue Plaques

- Career and Inspiration Links

- Contact

- Outreach

- Photo Gallery

- Bluestockings and Ladders