Electrical Association for Women, EAW

Download this brochure here.

Purchase EAW teatowels here.

In the early 1920s, electricity was just beginning to be introduced to the homes of the UK, and in 1924 Mrs Mabel Matthews – a British electrical engineer - had an idea to ‘popularise the domestic use of electricity’ in order to get women to use it more readily. But when Mrs Matthews presented her idea to the Institution of Electrical Engineers (IEE) in a paper entitled ‘The Development of Women's Interest in the Domestic Use of Electricity’ to fulfil the requirement for associate membership of the Institution, it was rejected. Undaunted, she submitted it to the Electrical Development Association, which also refused it. She next submitted her paper to the Women’s Engineering Society (WES), of which she was already a member, and got the enthusiastic response she sought.

On 12th November 1924, Lady Katharine Parsons – wife of Sir Charles Parsons, the industrialist and inventor of the steam turbine engine - convened in her home a special meeting of WES members, prominent electrical engineers and representatives of women's groups in order to form this Women's Electrical Association. Mrs Matthews explained her ideas: "When I was haymaking once during the war, an old farmhand came to me and said ‘Now ma'am, this is a job where you can work hard or you can work light. What you want to do is to work light'. I've never forgotten that, and I look round and see lots of women working hard when they might work 'light' with equally effective results. That is where electricity can help ..."

The Women's Electrical Association (WEA) held its first council meeting on 16th December 1924 and appointed Caroline Haslett – the secretary of the Women’s Engineering Society - its Director, a position she held until 1956. On 30th April 1925, to avoid confusion with the initials of the Workers' Educational Association, the name of the organisation was changed to the Electrical Association for Women (EAW), and it retained this name until the organisation closed in 1987.

The Association shared office space with the Women’s Engineering Society at 20 Regent Street in London, and Haslett used her growing influence and the Association’s strapline of ‘emancipation from drudgery’ to transform women’s role of domesticity through modern technology.

The EAW acted as a vehicle for the education of lay women about electricity and as an advisory body to the industry on matters of policy, asserting the need for safe and practical appliances in the home to reduce the burden of women's domestic work.

Essentially, it brought engineers and housewives together, acting as a liaison between (mostly male) engineers who did not understand what women wanted and housewives who could not follow the technical language.

Campaigns, Committees and Consultancy

The EAW devised and carried out numerous campaigns, the first of which in 1928 aimed to provide more socket outlets in homes. Campaigns included the design and performance of domestic electrical equipment, post-war reconstruction, air pollution and home planning.

In 1933 the EAW, together with prominent engineers, produced a report on "The Design and Performance of Domestic Electrical Appliances".

In 1933 Haslett secured a large grant from the Central Electricity Board to carry out a large-scale programme to educate women to make the best use of electricity in the home.

The EAW grew rapidly and branches were soon established in Glasgow, Birmingham and Manchester. In addition to branch activities designed to educate women about all aspects of electrical technology and its domestic use.

Indeed, education was one of the primary aims of the EAW, which it pursued through its journal, The Electrical Age, and through lectures, summer schools for teachers and school visits, amongst other activities. By 1933 the EAW was accepted as the primary communicator and educational establishment with regard to electricity and its domestic applications.

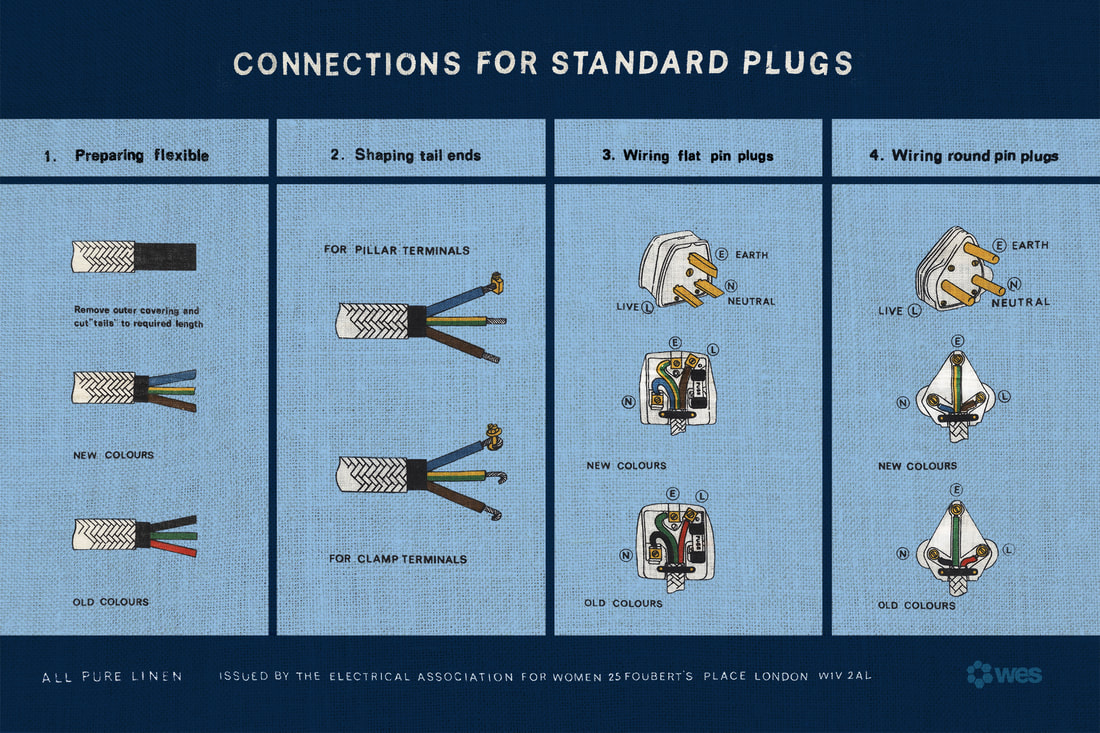

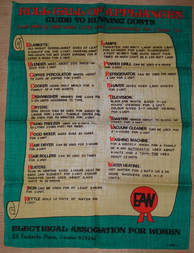

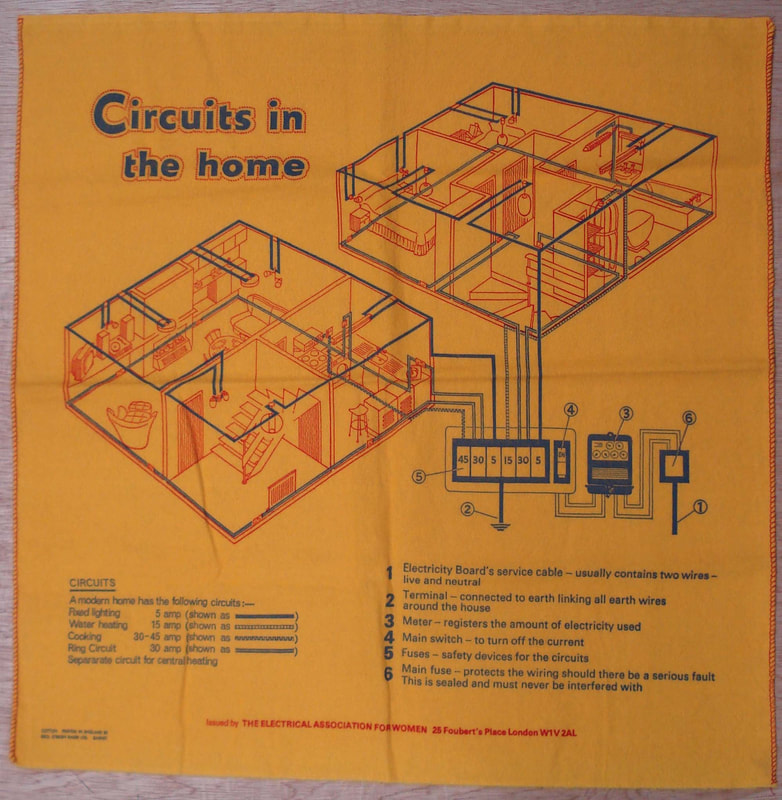

Electrical safety was another important facet of the programme, and in the 50s and 60s the EAW produced teatowels, dusters and pinnies to explain the principles of electricity and electrical safety to women. Three of these designs have been digitised and are available today as teatowels.

In 1935 the All Electric House was commissioned by the Bristol Branch of the Association and featured all kinds of electrical appliances and gadgets from an electric cooker, refrigerator and fires in every room to drying cupboards, electric clocks and food warmers.

The ‘EAW Electrical Housecraft’ course was given at most domestic science and technical colleges in the country. A certificate and diploma in electrical housecraft for teachers in schools and colleges followed instruction on "the application of electricity to household duties". The Diploma for Demonstrators and Saleswomen was first offered in 1931, and by the 1940s its Electrical Housecraft Certificate and diploma were recognised qualifications. A home worker's certificate was introduced for housewives and students, covering electricity generation and transmission, home installation of meters, fuses, switches, cookery, refrigeration, kitchen planning and similar applications.

The EAW continued to flourish after Haslett's death in 1957, but by the mid-1980s it was no longer attracting new members and was voluntarily dissolved in 1986. Its work in encouraging women to use electricity in domestic settings had been accomplished, and its pivotal influence in getting women out of the home and into the workplace had been achieved.

Purchase EAW teatowels here.

In the early 1920s, electricity was just beginning to be introduced to the homes of the UK, and in 1924 Mrs Mabel Matthews – a British electrical engineer - had an idea to ‘popularise the domestic use of electricity’ in order to get women to use it more readily. But when Mrs Matthews presented her idea to the Institution of Electrical Engineers (IEE) in a paper entitled ‘The Development of Women's Interest in the Domestic Use of Electricity’ to fulfil the requirement for associate membership of the Institution, it was rejected. Undaunted, she submitted it to the Electrical Development Association, which also refused it. She next submitted her paper to the Women’s Engineering Society (WES), of which she was already a member, and got the enthusiastic response she sought.

On 12th November 1924, Lady Katharine Parsons – wife of Sir Charles Parsons, the industrialist and inventor of the steam turbine engine - convened in her home a special meeting of WES members, prominent electrical engineers and representatives of women's groups in order to form this Women's Electrical Association. Mrs Matthews explained her ideas: "When I was haymaking once during the war, an old farmhand came to me and said ‘Now ma'am, this is a job where you can work hard or you can work light. What you want to do is to work light'. I've never forgotten that, and I look round and see lots of women working hard when they might work 'light' with equally effective results. That is where electricity can help ..."

The Women's Electrical Association (WEA) held its first council meeting on 16th December 1924 and appointed Caroline Haslett – the secretary of the Women’s Engineering Society - its Director, a position she held until 1956. On 30th April 1925, to avoid confusion with the initials of the Workers' Educational Association, the name of the organisation was changed to the Electrical Association for Women (EAW), and it retained this name until the organisation closed in 1987.

The Association shared office space with the Women’s Engineering Society at 20 Regent Street in London, and Haslett used her growing influence and the Association’s strapline of ‘emancipation from drudgery’ to transform women’s role of domesticity through modern technology.

The EAW acted as a vehicle for the education of lay women about electricity and as an advisory body to the industry on matters of policy, asserting the need for safe and practical appliances in the home to reduce the burden of women's domestic work.

Essentially, it brought engineers and housewives together, acting as a liaison between (mostly male) engineers who did not understand what women wanted and housewives who could not follow the technical language.

Campaigns, Committees and Consultancy

The EAW devised and carried out numerous campaigns, the first of which in 1928 aimed to provide more socket outlets in homes. Campaigns included the design and performance of domestic electrical equipment, post-war reconstruction, air pollution and home planning.

In 1933 the EAW, together with prominent engineers, produced a report on "The Design and Performance of Domestic Electrical Appliances".

In 1933 Haslett secured a large grant from the Central Electricity Board to carry out a large-scale programme to educate women to make the best use of electricity in the home.

The EAW grew rapidly and branches were soon established in Glasgow, Birmingham and Manchester. In addition to branch activities designed to educate women about all aspects of electrical technology and its domestic use.

Indeed, education was one of the primary aims of the EAW, which it pursued through its journal, The Electrical Age, and through lectures, summer schools for teachers and school visits, amongst other activities. By 1933 the EAW was accepted as the primary communicator and educational establishment with regard to electricity and its domestic applications.

Electrical safety was another important facet of the programme, and in the 50s and 60s the EAW produced teatowels, dusters and pinnies to explain the principles of electricity and electrical safety to women. Three of these designs have been digitised and are available today as teatowels.

In 1935 the All Electric House was commissioned by the Bristol Branch of the Association and featured all kinds of electrical appliances and gadgets from an electric cooker, refrigerator and fires in every room to drying cupboards, electric clocks and food warmers.

The ‘EAW Electrical Housecraft’ course was given at most domestic science and technical colleges in the country. A certificate and diploma in electrical housecraft for teachers in schools and colleges followed instruction on "the application of electricity to household duties". The Diploma for Demonstrators and Saleswomen was first offered in 1931, and by the 1940s its Electrical Housecraft Certificate and diploma were recognised qualifications. A home worker's certificate was introduced for housewives and students, covering electricity generation and transmission, home installation of meters, fuses, switches, cookery, refrigeration, kitchen planning and similar applications.

The EAW continued to flourish after Haslett's death in 1957, but by the mid-1980s it was no longer attracting new members and was voluntarily dissolved in 1986. Its work in encouraging women to use electricity in domestic settings had been accomplished, and its pivotal influence in getting women out of the home and into the workplace had been achieved.