|

To celebrate the centenary of the Women's Engineering Society, and the past 100 years of women in engineering, 2019 has been dedicated to a project called Engineer of the Week (EOTW) where each week we have focused attention on some of our Magnificent Women Engineers. In total we have produced 127 blogs! These blogs have been written by Nina Baker, and publicised through this and the WES social outreach channels of Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. Below are the biographies that have been produced, and the full list can be seen here.

Biographies can be found posted during different months of the year, and the links to these months can be found on the right hand side of this page: Biographies 1-9 are posted in the January 2019 archive 10-17 in the February 2019 archive 18-27 in the March 2019 archive 28-36 in the April 2019 archive 37-46 in the May 2019 archive 47-53 in the June 2019 archive 54-67 in the July 2019 archive 68-76 in the August 2019 archive 77-87 in the September 2019 archive 88-101 in the October 2019 archive 102-114 in the November 2019 archive 115-127 in the December 2019 archive

0 Comments

Engineer of the Week No.127: Constance Fligg Tipper (nee Elam) MA, DSc, FICST (16th February 1894 - 14th December 1995). For our very last EOTW for 2019, here is Constance Tipper, a very eminent metallurgist and a very rare example of an industry-standard test named after a woman. “Her work developed the new science of fracture mechanics, which is still used by engineers today to develop aeroplane wings that don't fall off and car axles that stay attached. So, today as the mechanical world around you doesn't fall apart, give thanks to Constance Tipper.” (http://www.engineerguy.com/comm/3731.htm) Constance was the daughter of a surgeon, William Henry Elam, and was educated at St Felix School, Southwold. She then went to Newnham College, Cambridge, gaining a third in part one of the natural sciences tripos in 1915. She first worked at the National Physical Laboratory’s metallurgy department, then at the Royal School of Mines, South Kensington, as an research assistant to Professor Harold Carpenter (1917). The Frecheville (1921–3) and the Royal Society Armourers and Brasiers (1924–9) eellowships enabled her to do research into the strength of single crystal aluminium. This was followed by research with Geoffrey Taylor, leading to the modern understanding of crystal plasticity. This period of work led to London University awarding her a DSc degree (1926). In 1928 Constance married George Howlett Tipper and moved to Newnham College, which had awarded her a research fellowship (1930–31). She remained there for over thirty years, during which time she occasionally lectured there and at the Chelsea Polytechnic. The university gave her testing facilities in the engineering department, and in 1947 the college elected her to be an associate fellow for three years.In 1949 the University made her a reader in mechanical engineering, which meant she was a full member of the faculty of engineering. Her war work led to her most influential research – on the deformation and fracture of iron and steel. This arose because theAdmiralty Ship Welding Committee wanted fractures in all-welded ships (eg the innovative Liberty ships) to be investigated. Constance Tipper found that their steel became dangerously brittle at low temperatures, and she developed her eponymous edge-notch test to predict whether the metal would behave in a brittle or ductile manner at service temperature. By 1948 she had authored or co-authored 12 academic papers and her wartime work led to her seminal book The Brittle Fracture Story (1962), the culmination of her career. She also enjoyed gardening, painting, and music. She died in 1995.  Engineer of the Week No.126: Mrs Christiana Rose (nee Cambell) (27 Dec 1792 – 10 Dec 1871) On her 227th birthday we remember one of our ‘oldest’ engineers of the week, iron-founder and machinery manufacturer, Christiana Rose. Christiana Campbell was born into a family whose business was ship chandlery and brass founding. Her father, Duncan Campbell had built the Old Foundry, Hull into one of the principal manufacturers of specialist machinery for the seed oil processing industry. Her brother died young and she seemingly stepped into the place he must have been expected to take learning to run the family firm. In 1812 the foundry was engaged in war work, casting cannons for the Battle of Waterloo. In 1818 Christiana married Captain John Rose and in 1823 they had their only child, Susan. When her father died in 1833 Mrs. Christiana Rose inherited ownership of the company. She employed Mr. James Downs, initially as a manager and later a partner in the company. By 1841 Christiana was a widow but still busy with her company. The company started to branch out from brass founding and in 1847 were advertising themselves as “Iron and Brass Founders, and Steam Engine and Boiler manufacturers”. There was a changing cast of partners in this period but Christiana was cer tainly at the helm and known for her expertise to the extent that she was taking on apprentices under her own name in 1861: “Indenture of apprenticeship Parties: (i) Michael Fenton, foreman oil miller of Sculcoates and Michael Fenton, his son, a minor (ii) Christiana Rose of Hull, iron founder and engineer. Trade of fitter and turner Wages to be paid as specified.” The company would have needed new employees at that time as in only two years, between 1861 and 1863, her Old Foundry had built and installed over one hundred double presses, all of which bore the name C Rose. Mrs Rose died in 1871 and in 1874 her grandson Mr. Campbell Thompson also became a partner and the company name became Rose, Downs and Thompson. The company was to trade under this name for over 100 years and became renowned throughout the world as a leading supplier of oil processing equipment. We do not know what she looked like as no portrait seems to exist but there is a ompany advert from around the time of her death and a photo of women working in the factory in the 1920s.  Engineer of the Week No.125: Marjorie Elsa Bell, BSc, Grad.IEE, C.Eng., MIISO, MIOSH, HonMWES (26th December 1906 - 10th June 2001) Today on her 113th Boxing day birthday, we remember WES President Marjorie Bell, electrical engineer and factory inspector. Marjorie Bell was born in 1906 in Edmonton, Middlesex. Her father was an engineering fitter and there were also 2 brothers, so she did not come from a well-off background. Her education was at a convent high school, from which she went straight to work at Cambridge Scientific Instrument Co, following a visit which piqued her interest in technical work. She also worked at the Bungay Gas and Electricity Co., where her duties even included shovelling the coal from which the gas was made. During the 1920s she attended Northampton Engineering College of the City university, thought to have been theirfirst female electrical engineering student and graduated with a BSc. During her course she was able to work in various electrical engineering firms. In 1933 she was a part time lecturer at Woolwich Polytechnic and lived with her mother in Wood Green, North London, and in 1934 started as Demonstrator in Worthing’s local authority electrical showrooms, which the local press seemed to find of great interest. 1936 saw her start on her long career as an HM Inspector of Factories, which took her not only to postings all over England but also, in 1947, to Palestine where she inspected fruit packing and canning factories, potash works and oil refineries. Although there were often bullets whizzing overhead, she considered her year in Palestine one of the happiest of her life. Her final post as an HMIF was as district inspector for London, following which she presumably had to retire from the Civil Service, at the then standard women’s retirement age of 60. She undertook various consultancies and committee work on industrial safety, including membership of the first EU CENELEC working group on electric toy safety and was the first woman to chair a BSI technical standards committee, again on toys. “I remember a story told me by Marjoie Bell. She became a factory inspector, in the days when factory inspectors were respected and feared. She went to visit a factory and chose to go there on her bike. She approached the gatehouse in style, only to be told by the guard, "Get off your bike and get out of the way quick, dearie, the factory inspector is coming!" To which she was delighted to reply, "I AM the factory inspector!" “ [As told by Marjorie to Jackie Carpenter] Having joined WES in 1932, she was on various local branch committees, national council and became president in 1957-58. In 1953, along with 2 other eminent members of WES, she was awarded the Coronation Medal and in 1972 was made an Honorary Member of WES. Marjorie was known for her gregariousness and continued to attend WES conferences almost to the end of her life. Her other interests included being an active member of the Soroptimists, keeping bees and two allotments until just before she died. She died in Enfield in 2001 and, characteristically, had made arrangements to leave her body to science and to have a non-religious funeral. On this day in 1919 (24 December) the Women's Engineering Society came into being as a company for the first time, according to the first WES Mem and Arts.

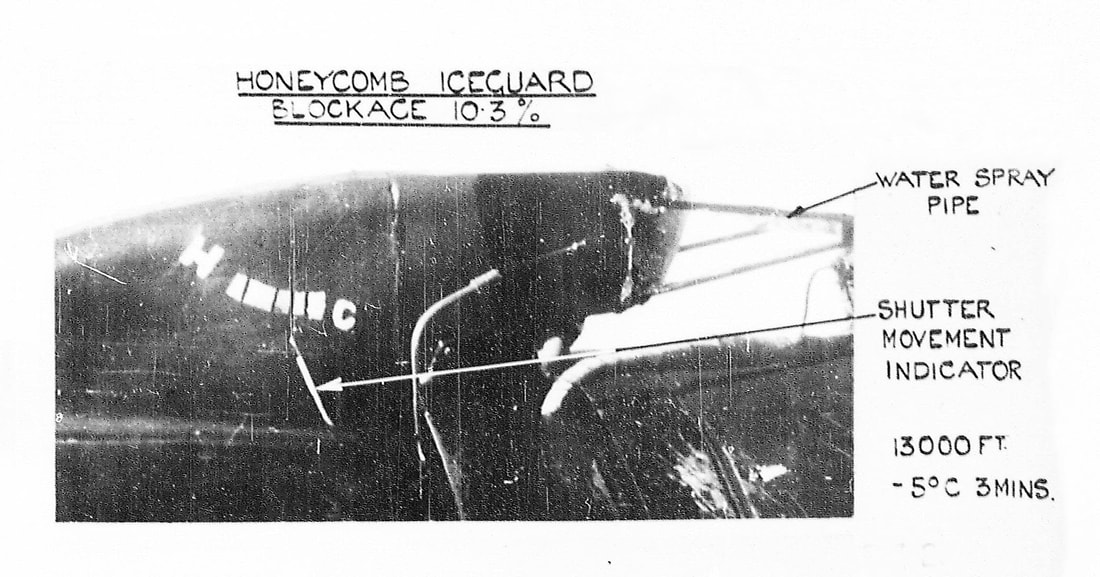

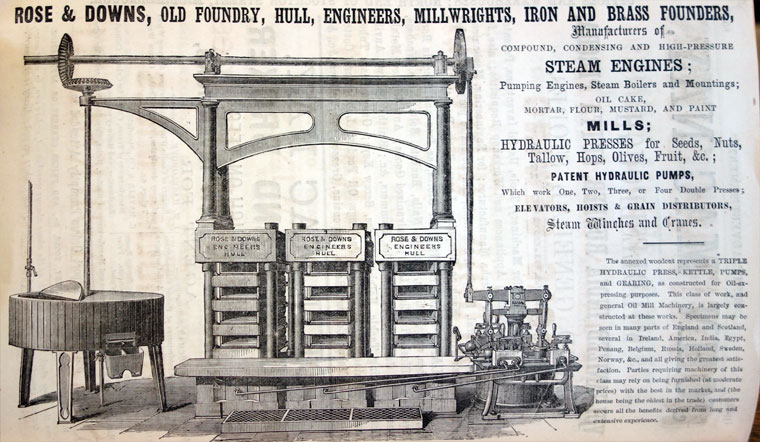

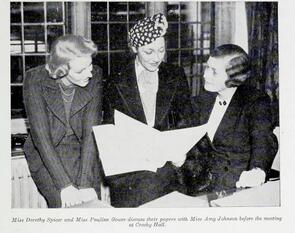

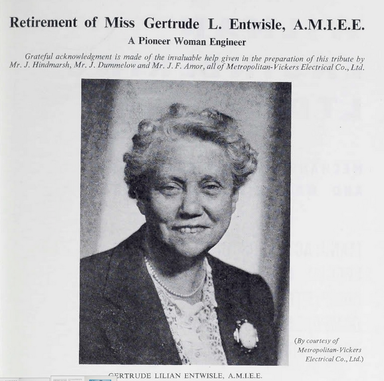

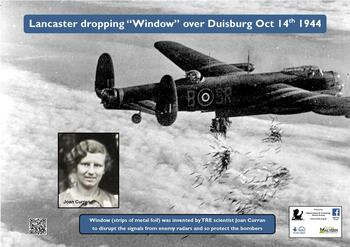

Engineer of the Week No.124: Blanche Coules Thornycroft AINA (23rd December 1873 - 1951) On her 146th birthday, we remember naval architect Blanche Thornycroft. Blanche Thornycroft was one of the earliest women to have a significant role in engineering in Britain, and the first woman to be elected to an Associate Membership of the Institution of Naval Architects. For a fuller article, by Keith Harcourt, see http://journal.sciencemuseum.ac.uk/browse/issue-10/blanche-thornycroft/ , from which the information for this EOTW profile has come. Thanks also for the pictures from The Classic Boat Museum, https://www.classicboatmuseum.com/ Born into a privileged position as daughter of John Thornycroft, shipbuilder, there is no record that Blanche had any formal school or university education in the maths and sciences which she would obviously have needed for her future work. Since she was born in an era when ‘learning by doing’, with a professional engineer as Master, her immersion in the family business as an informal ‘pupil’ would not have been as unusual a way into engineering as it became 40 years later. The Thornycroft family home at Bembridge on the Isle of Wight, included facilities to explore the design of ships. An apparently decorative garden pond included sophisticated measuring equipment so that it could be used as a testing tank. Ship models were towed through the water at a controlled velocity, and measuring instruments were in a nearby building. One of the best images of Blanche is of her holding one of the discs from the recording device, made by the Cambridge Scientific Instrument Company, which recorded the performance of the model boat in the ‘Lily Pond’ tank. These discs were covered in soot which was scratched off to record the behaviour of the test vessel, in much the same way as early phonograph records were made. She worked with her father and brother on a variety of naval ships’ and powercraft designs, including a design for a coastal motor torpedo-boat and the behaviour of wire hawsers during WW1. In 1919 the AGM of Institution of Naval Architects elected to her to be its first female Associate Member, although she seems not to have been active in the Institution. The last recorded date when she was doing her naval architecture work was in 1935, when she was working on a ‘special launch’ for the RAF. She never married but her recreational interest in sailing, and membership of the local sailing club continued until her death in 1951.  Engineer of the Week No.123: Dorothy Norman Pearse (née Spicer) (31 July 1908 - 23 December 1946) In the week of her tragic death 73 years ago, we remember aeronautical engineer, Dorothy Spicer. Dorothy Spicer was an aviator and aeronautical engineer. From a privileged background she had a good education in Belgium and at University College London. As soon as she ‘came of age’ (21), she started her flying training at the London Aeroplane Club, Stag Lane. She quickly got her A licence as a private pilot and soon after obtained her B and C licences, allowing her to fly as a commercial pilot, completing the ‘set’ with the D licence (qualifying to inspect and pass as airworthy both engines and planes) in 1935, the first woman to do so. These qualified her at all levels then available, as a ground engineer as well as pilot. During her first flying lessons she met Pauline Gower with whom she would form a lifelong friendship as well as business partnership. They joined the, then popular, charity air circus display circuit, initially he Crimson Fleet air circus and later the British Hospitals' Air Pageants. Dorothy became something of a celebrity and undertook many speaking engagements relating to her flying expertise. For a couple of years she and Gower ran an air taxi business but it was ultimately not very successful and ceased in 1938, the same year in which she married and also went to work for the Air Registration Board. In 1939 her daughter, Patricia, was born and the following year Dorothy joined her husband at the Royal Aircraft Establishment, Farnborough. Her work was as an air observer and research assistant, and her name is on two reports: one on tests of de-icing measures and another on a deflector plate to prevent sand entering the engines of the Hurricane plane. After the war Dorothy and her husband went to Rio de Janeiro where he had got a job with British Aviation Services Ltd. In December 1946 both of them were killed when the plane, in which they were passengers, crashed into a mountain on approach to Rio de Janeiro. Dorothy had been an active member of the Women’s Engineering Society and its aviation section from 1931 and contributed articles to The Woman Engineer including "Selection and Treatment of Steels for Aero-Engines", in 1937. Her death was much mourned, coming as it did so close to the death (in childbirth) of her friend Pauline Gower. The Royal Aircraft Establishment operated a Dorothy Spicer Award for several years after her death.  Engineer of the Week No.122: Mrs Emily ‘M.M.’ Dunn, MIQ (nee Harris) (10th January 1890 - 20th December 1967) On the 52nd anniversary of her death, we remembe Emily Dunn, quarrywoman. Astonishingly Emily Dunn is one of two Yorkshirewomen running their own quarries in the first half of the 20th century, the other being Anne Greaves. She was born in Hull, into a complex family of stepsiblings in which both parents had had previous marriages. The family was reasonably well off as her father was a land agent. Nothing is known of her education but the family would probably have been able to affor for her to remain at the local school into her teens. In 1912 she married Eward Crowhurst Dunn, who was manager of the Hatfield Cooperative Society grocery. It is unclear how she came to be a quarry owner in the first place, but at the very young age of 23 she was already the proprietor of a small quarry in Dunsville to the north east of Doncaster, Yorkshire, when her quarry manager died and she found herself forced to take over running it. She had neither technical experience nor capital and the quarry was running on a very small scale: 3 men with shovels, riddles and wheelbarrows. To make her life even more difficult, she was trying to sell quarry sand and gravel in a district where builders were more accustomed to river gravel. To overcome this, she travelled south to find contractors willing to buy her products. The quarries also produced unexpected materials, including 2 human skeletons which immediately disintegrated, but also various fossils and she donated 160 fossils of Pleistocene bones found in her quarries to the Kingston upon Hull Museum in 1927. The next problem was transport, so she hired and then bought steam traction engines but the roads authorities would not let these colossally heavy vehicles on many roads and bridges, so she had a railway siding built to her quarry but found that the rates charged by the rail companies prohibitive. This forced her back to road transport and she built up a fleet of petrol motor lorries. Even to produce satisfactory grades of sand and gravel Mrs Dunn was obliged to turn to her own ingenuity to “….invent and install what rather looked like Heath Robinson attempts at washing plants.”. By 1929 she was employing from 30-50 men at the quarry and had upgraded her machinery to “...much larger and more up-to-date washing and breaking plant and layout. All these were under separate power but this year I have procured a cold start crude oil engine and have connected the whole of my washing and breaking plant under this one power which is working very satisfactorily and cheaply. I have also a paraffin / petrol locomotive for drawing the cubic yard tip wagons on light railway, which has enabled me to dispose of three horses and the necessary attendants. All this has been a big worry to me, as to a large extent I am my own engineer and technical adviser.” In around 1929 she diversified into concrete products, but not long afterwards she put the quarry on the market and she and her husband moved to Filey where they ran a mixed farm for about 10 years. In 1930 she exhibited her products at the Scarborough conference of the Institute of Quarrying, of which she was one of the first two women full members. She was also active in the Women’s Engineering Society and contributed articles about her work to its journal. Emily Dunn died in 1967, leaving the not inconsiderable sum for that time of £250k, but had apparently spent the last years of her life as a recluse, having been widowed in 1952.  Engineer of the Week No.121: Mrs Mary Patricia Kendrick (nee Boak), BA, CICE MBE (2nd May 1928 – 8th June 2015) Whenever you hear of cities flooding or read about the potential for climate change and sealevel rise to flood our major cities, you can thank Mary Kendrick for her life’s work on the Thames and Mersey river systems. Mary Kendrick was the foremost tidal engineer of her generation in the UK and a respected authority worldwide, despite not originally training in one of the engineering disciplines. She was born and educated in the English Midlands and gained a joint honours BA in geography and economics from the University of Nottingham in 1951, the same year that she married fellow student Les Kendrick. In 1956 applied for a secretarial post at Hydraulics Research Station Ltd, but her interviewer spotted that she was actually qualified to join them as an Assistant Experimental Officer, which was the start of her career-long work with HRS. Her first work with HRS was on their contract to investigate and propose solutions for Mersey Docks and Harbour Board into the deteriorating tidal volume and increasing silting in the Mersey estuary. Mary undertook field survey work in survey vessels measuring currents and following sediment transport pathways using radioactive tracers and fluorescent dyes. This work led to the paper she published with a colleague, Alan Price, ‘Field and model investigations into the reasons for siltation in the Mersey estuary’, in the Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers in 1963, earning them the 1964 Telford gold medal, for which Kendrick was the first woman to receive this award. The paper is still considered a seminal work and set the scene for her continuing career in this field. In 1968 Mary was appointed to lead HRS’s team on the Thames flood prevention project, which culminated in the construction of the Thames Barrier in 1982. This involved not only an enormous amount of field survey work but also a great deal of public and political consultation, arguably the more difficult part. This was also the period when she was consulted on the hugely controversial proposal for a third London airport on the Maplin Sands, off the Essex coast, as well as various overseas projects. On her retirement from HRS in 1988 (as a Principal Scientific Officer) she was awarde the MBE and was appointed by the UK government to become the first ever woman to be the acting conservator for the Mersey, a position created abouit 200 years ago to safeguard the navigation of the river in Liverpool. She was the first woman to take up the post, which was usually reserved for admirals. She was also active on behalf of the UK, in the Permanent International Association of Navigation Congresses, only relinquishing that role shortly before her death. Mary Kendrick joined the Women’s Engineering Society in about 1970 and wrote several technical articles about her work for its journal as well as delivering the 1983 Verena Holmes lecture series, which were aimed at encouraging schoolgirls to enter engineering.  Engineer of the Week No.120: Madeleine Marie Nobbs (Mrs. D. Moody) MIMechE, MIHVE, MRSanI (14th December 1914 - 10th December 1970) On her 105th birthday, our woman in engineering today is Madeleine Nobbs, building services engineer. Madeleine was born in 1914 and educated at a convent school. Her father, Walter W Nobbs was very well known in the heating and ventilation engineering world and his father had also been a civil engineer. She very reluctantly started her working life as a shorthand typist but persuaded a firm of heating and venitlation engineers that she would be suited to the drawing office, where she started as a tracer. Her studies at Borough Polytechnic enable her to progress to H&V work for an architect’s office including estimating and supervising installation. During the war she designed air raid shelters. Then she found a variety of jobs that allowed her to get practical bench and site experience until she was a fully qualifed engineer and joined her father’s firm as a junior partner. Her father died in 1954 in the middle of a major contract on the rebuilding of the Old Bailey after war damage, so Madeleine stepped up to become senior partner and take over the firm on her own account and complete the heating and ventilation contract. Around the same time she met her future husband, Denis Moody, also an engineer and they married in 1961. Unfortunately, he died a few years later and she immersed herself in major building work to convert an old barn into a home, doing most of the work herself, to get over her loss. She joined the Women’s Engineering Society in 1941 and was soon active on the council, becoming president in 1959-60. She contributed many papers on heating and ventilation to The Woman Engineer and gained full membership of a number of engineering institutions. She was very gregarious, loved the theatre, huge houseparties at her home, fast cars and outrageous hats. Sadly, she died suddenly at the age of only 56, in 1970.  "Engineer" of the Week No.119: Augusta Ada King, Countess of Lovelace (née Byron; 10 December 1815 – 27 November 1852) On her 204th birthday we remember Ada Lovelace, mathematics writer. In October each year, many university departments of computer science hold an “Ada Lovelace Day” to encourage their female students and staff. You will note that October is neither the month of her birth nor death – it has been picked purely for academic term time convenience. I have felt it necessary to include Ada as one of the “Engineer of the Week” profiles because so many people consider her an important icon in promoting STEM work to girls and women. Ada Lovelace is very well known even amongst the general public who are not connected with any STEM fields – she is often the person named if they are asked to name a female engineer from the past. As such, I have not provided a detailed biography of Ada, since there are many to be found online and in books. There is a computer programming language named after her – Ada being a high level development of the Pascal language. If you Google “Ada Lovelace”, some 1.7 million results appear and the following are a selection of the epithets applied to her from the first page of results: Computing visionary. Prophet of the computer age. Computing pioneer. Powerful symbol for modern women in technology. Computer Programmer, Mathematician. The world's first computer programmer. Associate of Charles Babbage, for whose prototype of a digital computer she created a program. She has been called the first computer programmer. World's First Computer Programmer. There are far more hagiographic pieces about her than there are critical considerations of her work. For a detailed, critical examination of the many claims made for her, read The Renaissance Mathematicus ( https://thonyc.wordpress.com/2018/11/03/no-simply-no/ ) and for a more enthusiastic survey of her work look at Untangling The Web ( https://www.wired.com/2015/12/untangling-the-tale-of-ada-lovelace/ ). I do not consider her to have been an engineer – a mathematician, and a competent one - yes, but not one with significant original thoughts in that field. A talented writer, explainer/interpreter – also yes. In the matter of being the first to propose algorithms for general use of the mechanical computing machines – it is almost certain that both Babbage himself and (much earlier) Gottfried Leibniz had had the same ideas - but nowadays hers are the ones that are so widely known. She came from deep privilege – the celebrity daughter of a celebrity poet-hero, the indulged wife of a rich man, beautiful, more highly educated than almost any woman in the country at the time – all of these contribute to her fame then and now. But we do her undoubted talents no favours if we exaggerate them and she herself would probably have been the first to do a critical analysis of today’s many fawning profiles of her. Her lessons to today’s young people who might enter STEM work should be: read widely, seek concrete evidence, and ask what might be possible next.  Engineer of the Week No.117: Rosemary Ethel Elizabeth West (nee Lambert) MA MIEE, CEng (8th December 1928 - 6th February 2013) On what would have been her 91st birthday we celebrate the work of Rosemary West, WES president and pioneering computer engineer. Rosemary was born in 1928 in Lyme Regis, Dorset, the second daughter of Edward William Lambert, who followed his father into the family’s law firm in Burma before entering the British colonial service and rising to become the Director of the Crown Office in Burma (Myanmar). She was educated a number of boarding schools in the UK and even in Burma and India during the war years and was accepted to read maths at Oxford, where she was a rowing Blue. Having had a vacation job with Metropolitan Vickers, she changed to engineering and graduated in Engineering Sciences from Somerville College, Oxford, in 1951, only the third woman ever to do so from Oxford. She went straight into a graduate apprenticeship with GEC Ltd in Coventry and by 1957 was one of their electronic development engineers in the Applied Development Laboratories, working on specialised test equipment. The following year her daughter was born which led GEC to sack her, following which she taught in a school and also in Kirkcaldy Technical College. In 1971 she and her husband set up Westek Engineering Ltd, in Ibstock, Leicestershire, developing microcomputer systems, interfaces and computer-controlled transducers for test equipment and industrial controls. By 1967 she was a chartered engineer and a full member of the IEE. By the time she became President of the Society she was working as a microcomputer specialist in the Computer Centre at Loughborough University of Technology. Rosemary joined WES in 1950 and by 1961 was chair of the Midlands branch, becoming the society’s president in 1982-3. She wrote several pieces for The Woman Engineer to stimulate members to think about the future of the Society. Given her own experiences of being made redundant and of trying to fit in a career with a family she was very interested in the whole issue of women returning to work after career breaks which must have tied in very well with her successor, Professor Daphne Jackson’s similar interests. She wrote an article, Engineering Management for Women, for the IEEProceedings and produced a WES booklet for schoolgirls, What is Engineering? She died in 2013, in the Isle of Wight.  Engineer of the Week No. 116: Maria de Lourdes Ruivo da Silva de Matos Pintasilgo, GCC GCIH GCL (18 January 1930 – Lisbon, 10 July 2004) Pintasilgo was a chemical engineer and Portuguese politician. She was the first and to date only woman to serve as Prime Minister of Portugal, albeit for only 100 days, in 1979. Educated at a Lisbon secondary school, she was an enthusiastic member of the compulsory youth organisation, Mocidade Portuguesa Feminina, and also joined Acção Católica (Catholic Action). She then went to the Instituto Superior Técnico graduating in industrial chemical engineering in 1953. Whilst there she became active the Catholic's women's student movement, which was the start of her political interests. Her first job after university was as a graduate trainee with the national Nuclear Energy Board. She then moved to one of Portugal’s oldest and largest engineering conglomerate with interests in cement plants, Companhia União Fabril. By 1954, she held the position of chief engineer of the research and projects division, from which she became responsible for the company's technical journals, until she left in 1960, thus ending her period as an engineer. Her political career developed with various organisations in the Roman Catholic laywomen's movement whilst working for the government's program for development and social change. In 1974 she was appointed secretary of state for social welfare in the first provisional government following the revolution, rising to become Minister of Social Affairs by early 1975. In 1975, Pintasilgo became Portugal's first Ambassador to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, UNESCO. In 1979 the Portugese president asked her to become Prime Minister of the Portuguese caretaker government, for a period of 3 months, making her the 2nd woman prime minister in Europe (after Thatcher). Although her term of office very brief she was able to use it to introduce some social welfare reforms and later was elected to the European Parliament. She died in 2004 but since 2016, the Instituto Superior Técnico awards the Maria de Lourdes Pintasilgo Award to 2 female engineering graduates. Engineer of the Week No. 115: Isabel Hodgson Hadfield, MSc, DiplEd., MSPA (29th January 1893- 6th February 1965)

Chemical engineer Isabel Hadfield spent most of her career in research at the NPL. We do not generally think of fabrics as engineering materials these days but in the early days of aviation, cotton and linen were the usual coverings for aeroplanes’ wood-framed structures. Her research, initially for this purpose but later for more general industrial needs, looked at the effects of the mild acids used to process cloth and of sunshine on cotton fabrics. Her approach was entirely that of the engineer: the physical and chemical structures and properties of the material under consideration in respect to the stresses and strains which would be required of it. Born in Hampshire, where her father was a schoolmaster, she was mainly raised in north east London. She graduated from East London College (now Queen Mary College) with a BSc in chemistry in 1914, then took a Diploma of Education and became a chemistry mistress for the Birmingham Education Council. In 1917 the demands of the war effort led her to join the National Physical Laboratory, where she would remain for a full career as a researcher. Her war work was, as discussed already, on the deterioration properties of cotton and linen in aeronautical use, on which she co-authored her first paper in 1918. In 1923 she gained an MSc in chemistry from East London Technical College, with her dissertation being on ‘doped’ fabrics. Her work on cotton, now for industrial purposes, continued through the 1920s, including the publication of 4 more papers, one of which she gave at the at Conference for Women in Science and industry, at the Empire Exhibition, Wembley,16th July 1925, later published in The Woman Engineer. In 1927 she was part of the NPL total solar eclipse expedition, for which she was to have provided the colour and photometric photographs, except that the entire proceedings descended to “a solemn farce” due to the total cloud cover for most that day! Her later career took her into metallurgy and research methods and by 1947 she was the most senior woman at NPL: a PSO in the Metallurgyy section, and was publishing on a range of related topics. In 1933 she was one of the founder members of the Micro-chemical Group within the Chemistry Society (now RCS) and in 1944 was admitted as member to Society of Public Analysts. In 1948 she was the only woman on the committee developing BS1428 on microchemical analysis standards. She had a full career at the NPL, retiring at the usual age for women in 1953, with the rank of Principal Scientific Officer. She never married and died in Winchester in 1965.  Engineer of the Week No.114: Catherine Anselm ‘Kate’ Gleason, MASME (25 November 1865 – 9 January 1933) In the week of her 154th birthday we remember the USA’s first woman engineer, “Concrete Kate” Gleason, mechanical engineer and house builder. Kate Gleason, although one of the first women admitted to ASME (1918) and the first to be admitted to Cornell (1884) to study engineering, never completed an engineering degree. Much of her engineering was learned the practical way, from childhood work in her father’s factory, Gleason Works, which specialised in gear-cutting machines. After many years helping her father’s firm, latterly as a salesperson, in 1914 she left to take up an appointment as receiver of bankruptcy for the Ingle Machine Company. She is believed to have been the first woman to take on such a role, but the first woman to do so. She was able to turn the company around, repay its debts and return it to its stockholders within a year. From this success she moved on to building factories and housing in the East Rochester (New York state) area. She worked with local architects to design low cost housing using her own ideas for poured concrete construction, materials selection, and site management. Taking a lesson in the producton methods of the big automobile factories which she had visited selling her father’s machines, her sites were run more like Ford’s production lines, with every worker only having exactly those materials required for the immediate piece of work. The houses were in a Dutch style set in a garden suburb layout. Her concrete houses led to her becoming the first female member of the American Concrete Institute. She also built some houses in Sausalito, California and at her winter home in Beaufort, South Carolina where she had plans to make a community of garden apartments for artists. However only 10 of these were completed at the time of her death, in 1933, from pneumonia. She never married, considering marriage an impediment to her professional interests. Her summer home, the island of Dataw, she left to her secretary. She seems to have had a couple of patents but not to have made much commercial use of them. The University of South Carolina’s archives hold 2 home movies made by Kate, unfortunately none of the shots include any of her professional work.  Engineer of the Week No.113: Beryl Catherine Platt, Baroness Platt of Writtle CBE DL FRSA FREng HonFIMechE (née Myatt) (18 April 1923 – 1 February 2015) As WES nears the end of its Centenary Year we remember the work of Beryl Platt who helped establish the Women Into Science and Engineering Year in 1984. Baroness Beryl Platt was of the generation of women for whom the Second World War opened up a brief window of opportunity in engineering, only for the ‘marriage bar’ to shut it again. Her mathematical talent took her from Westcliff High School for Girls to Girton College Cambridge, where she was only the 9th woman ever to pass the mechanical science tripos with honours (1943) under the wartime accelerated degree programme. Cambridge of course did not at that time actually award the degrees which women had earned. The same programme directed her into aeronautical engineering at Hawker Aircraft Ltd, as a technical assistant in the experimental flight section of the Design Office. Her work analysed data from test flights of fighter planes, including the Hurricane, work which she later recalled as “I couldn’t ever let anyone down. We were testing and producing fighters which really made a difference to winning the war”. In 1946 she became a technical assistant in the performance and analysis section of British European Airways’ Project Department, testing new aircraft and ensuring compliance with UK and international safety regulations. However, in 1949 she married and the convention of those times was that married women retired from their paid employment. This, though, was the start of her long and productive political career from parish councillor, via the county council, to becoming an active Conservative peer in the House of Lords and chair of the Equal Opportunities Commission. Although her own career as an engineer had been brief, she made it her business to do much to support the opportunities for women in engineering. Her work setting up the Women Into Science and Engineering Year in 1984 and its subsequent programmes for girls and women, included rejoining the Women’s Engineering Society and serving on numerous engineering education related boards. Her eminent career in support of equal opportunities for women and technical engineering education led to many honorary doctorates, the CBE in 1978 and the Freedom of the City of London in 1988.  Engineer of the Week No.112: Elizabeth (Betty) Laverick (nee Rayner) OBE, FIEE, CEng, FInstP, SMIRE, HonFUMIST (25th November 1925 – 12th January 2010) On what would have been her 94th birthday we remember electronics engineer, Betty Laverick. Elizabeth Laverick was born in Amersham, Buckinghamshire, in 1925, into a family of second-generation chemists, her father, William Rayner, being a manufacturing chemist. Her mother Alice Maria Garland assisted with the administration of the business. She won scholarship to Dr Challoner’s Grammer School nearby, then a co-educational school, where she became the only girld in the Higher Schools Certificate class. She and her older sister were both strongly encouraged by their parents to go to University but Elizabeth’s November birthday meant Durham could not take her until 1943. She spent that year as a scientific civil servant at the Radio Research Station near Slough, as a Technical Assistant, Grade III. She graduated from Durham in 1946 with a degree in Physics and Radio (a special wartime course) and stayed onto to a PhD on “ Dielectric measurements at audio frequencies using a differential”. She married a fellow student, Charles Laverick in 1946 and in 1951 they were both hired by GEC Stanmore (Marconi Defence Systems Ltd.) where she worked as a microwave engineer, working on guided weapons systems. In 1954 Laverick moved to Elliott Automation (part of Elliot Brothers) as a microwave engineer, gaining commercial experience in microwave instruments and rising to become the general manager of Elliott Automation Radar Systems. She published papers on some of her work and was involved in the development of the airborne Early Warning system later known as the Nimrod. In 1971 she moved away from practical engineering to become the first female deputy secretary of the Institute of Electrical Engineers, which gave her the opportunity to pursue her interests in applying her management expertise to the Institution’s career development for members. In her reitrement in 1985 Laverick joined the Court of City University, as well as doing some work as a consultant in advanced manufacturing in electronics Having joined the Women’s Engineering Society in the late 1950s, meet other women engineers and promote the career to girls, she soon joined the London Branch committee and the national council and became the society’s president in 1968/69. She continued her active involvement as Honorary Treasurer and was editor of the journal for 7 years. As well as her OBE in 1993 she was also honoured with an honorary fellowship at UMIST and became a liveryman of the Worshipful Company of Engineers,. Her leisure interests included tapestry and music and she became interested in nursing homes for the elderly, eventually selling the family home in Amersham for that purpose. She married again shortly before she died, to Peter, her long time companion. She died in 2010.  Engineer of the Week No. 111: Jean Marion Taylor, BSc, FIWSc (29th February 1924-18th 1999) Today we remember Jean Taylor, for her work the timber preservation industry. Jean Taylor was generally described in her lifetime as an entomologist but, although that was the source of her expertise, perhaps today she might be considered to have been an applied biologist or bio-engineer. It remains commonplace to think of engineering as only being about the use of metals, and perhaps concrete, but wood is just as much an engineering material, requiring the same engineering mode of thought, in order to use it effectively, which she was certainly doing in her work. Jean was born, on a Leap Day, into a modest background in Cardiff, Wales, where her father was a tobacconist and she had two younger siblings. She served in the WAAF during WW2, working on air-frame maintenance and becoming a skilled fitter. After the war she went to Cardiff University and gained a degree in zoology, which took her to her first job, in the Entomology Section of the government’s Forest Products Research Laboratory in 1949 to work for Dr. R.C. Fisher. Her work was on the prevention and control of wood-boring insect infestation. She led the evaluation of the newer generation of insecticides and was particularly concerned with the development of laboratory testing technology and how to apply laboratory results to industry. Her expertise led to involvement in drafting international standards with the European Standards Organisation, CEN, and in the International Research Group on Wood Preservation, and collaborations with colleagues in Australia. She published about 14 papers on various aspects of wood preservation from 1960-1991. After 20 years at the FPRL she moved into industry, becoming the technical director at Protim Ltd., where one aspect of her work was the investigation of insect resistance of wood and plastic composites. From becoming the Institute of Wood Sciences’ first female fellow in 1962, she was active in the organisation, on many committees, setting up its newsletter and becoming its president in 1986-88 Colleagues remembered her not only for her exacting attitude to her work but her skill in explaining its complexities in a very clear and engaging way. Jean was also an active golfer and member of the local branch of the Soroptimists, whose secretary and branch president she was for several years.  Engineer of the Week No.110: Peggy Lilian Hodges (11th June 1921 – 21st November 2008) OBE, MA, CEng, FRAeS, FIMA, HonFIET On the 11th anniversary of her death we remember defence electronics engineer Peggy Hodges. Peggy Lilian Hodges, was born in London in 1921 into modest circumstances which cannot have improved when her father Ernest, a credit draper, died when she was only 4 years old. She was educated at the Westcliff High School for Girls, in Essex and then gained a modest State Scholarship to take a degree in mathematics from Girton College, Cambridge in 1943. Her first job was as a radio engineer with Standard Telephone & Cable, where she worked on airborne communications and the ILS blind beacon landing equipment. In 1950 she joined the GEC Applied Electronics Laboratories at Stanmore, Middlesex, as a microwave and systems engineer, working on guided weapons. Missile projects included Red Dean and Sea Dart, which relied heavily on the systems assessments produced by Hodges and her team. She became an expert on simulation and systems, including assessments of random aberrations, types of dish stabilisation, target glint and sea reflection problems. She progressed to become Systems Manager and then Project Manager of the Guided Weapons Project (Sea Dart Guidance) in the Guided Weapons Division. She was consulted by other laboratories and government departments and was sent on government missions to the USA. She was a member of the Radome Electrical Performance Panel for Guided Weapons and aircraft for the Ministry of Aviation. Among other projects, Hodges worked in the Underwater Weapons Division on trials planning and analysis for air-launched guided torpedoes, and later worked on simulation, identifying problems affecting guided weapons systems. Her work on guided weapons was featured in a BBC documentary in the 1960s, when she was filmed at work at the Ministry of Defence’s guided-missile firing range at Aberporth in Wales. In 1971 she was promoted to Deputy guided weapons project division manager (systems) at Marconi space and defence systems, within GEC. Her division did general performance work, systems studies, simulations, trials planning analysis. Hodges formally retired from GEC in 1981 but continued to do general systems consultancy for the Guided Weapons Division of Marconi Space and Defence Systems (MSDS), Stanmore. In retirement she did voluntary work in an old people’s home, and was involved in the setting up, by the Institution of Electrical and Electronics Incorporated Engineers, of a new annual competition: the Girl Technician Engineer of the Year, later Young Woman Engineer of the Year. She was Chair of the Caroline Haslett Trust set up to encourage girls, by means of scholarships and competitions, to take up careers in engineering, and in 1982-3 was President of Soroptimist International St Albans and District. She was also a member of the Fawcett Society, was interested in ballet, opera and classical music. Having joined the Women’s Engineering Society in 1960 she soon became a council member and was the society’s president in 1972-3 In 1959 she became an Associate Fellow of the Royal Aeronautical Society and a full Fellow 10 years later, having already been the first woman to take the Chair at a meeting of the Royal Aeronautical Society, when the subject under discussion was "Guided Weapon Simulators." In 1970 she received the Whitney-Straight Award for outstanding performance by a woman in the field of Aeronautics, and 2 years later she was awarded the OBE in the Queen’s Birthday Honours, for her contribution to guided weapons technology. In 1994 Hodges became the first female honorary fellow of Institution of Electronics and Electrical Incorporated Engineers (IEEIE, later the IET). She died in 2008 in Buckinghamshire and legacies include the “Peggy Hodges Prize” for the highest performing female student completing the second year of a full time MEng/BEng Engineering degree at the University of Hertfordshire.  Engineer of the Week No.109: Gertrude Lillian Entwisle BSc, AMIEE (1892 -18th November 1961) On the 58th anniversary of her death, today we remember electrical engineer Gertrude Entwisle. A Lancashire lass, Gertrude was educated at Milham Ford School, Oxford and then at Manchester High School For Girls, where she was awarded an Exhibition to enable her to attend Manchester University to study physics. She was one of the first women to attend engineering lectures at the University, after the engineering faculty decided to open its classes to women mid-way through her physics degree. She was the first woman to be admitted to the technical staff of British Westinghouse, the first woman member of the Society of Technical Engineers and the first Student, Graduate and Associate Member of the IEE (now the IET). She owned a threewheel Harper Runabout – acurious blend of motor-trike and small car. She worked mainly on the design of DC motors and generators until 1923 when she spent about 20 years working on AC before returning to DC motors during the Second World War. One of her largest designs was the DC motor for a motor generator flywheel set on the winding gear at Broken Hill mines in Australia. Towards the end of her career she became a specialist in large exciters for coal and hydropower stations. An early member of WES, she became Vice President in 1937 but yielded the presidency for 1938 to Caroline Haslett so that the latter could be president during the society’s 21st birthday year, but was then president for 1942. She retired from Metropolitan-Vickers in 1954, after a 39-year career, and died in 1961.  Engineer of the Week No.108: Pauline Mary de Peauly Gower MBE (Mrs Fahie) (22 July 1910 - 2 March 1947) In Remembrance Week we remember Pauline Gower who set up and commanded the women’s Air Transport Auxiliary, in WW2 Pauline Gower, although from a privileged background, had to find her own way in her chosen career as a pilot, due to family opposition. She supported herself giving music lessons, in order to take her first flying lessons, gaining her A licence (private pilot) in 1930 and the following year got her B licence (commercial pilot) after lessons at the London aeroplane club, Stag Lane. This was where she met Dorothy Spicer with whom she went on to set up a commercial flying company, with a Gypsy Moth plane. Whilst Pauline went on to get every possible pilot’s qualifications, Dorothy did likewise in the aero-engineering side. However the business was short-lived and they went to join various air-display teams which were popular at the time. In 1938 she was invited to become a member of the Gorrell committee on aircraft safety. As the Second World War approached, Pauline campaigned for women pilots to be allowed to do their bit. In 1939 she was appointed a commissioner of the Civil Air Guard. Later that year she was appointed as an Air Transport Auxiliary second officer and given the job of forming a women's section. The number of women pilots rose to 150, with a few flight engineers too, and they eventually flew all types of aircraft, from light trainers to four-engined bombers. Some of ‘her girls’ even gave their lives, including the most famous of all, her friend Amy Johnston. Pauline campaigned for and finally obtained the same pay for her women pilots as the men received for doing the same work, and was awarded an MBE in 1942. Her exceptional leadership skills led to her appointment as a director of British Overseas Airways, the first woman in such a senior position in any national airline. Pauline joined the Air Section of the Women’s Engineering Society in 1931, and was an active member, speaking, writing articles for The Woman Engineer and promoting flying careers to members. In 1935 she joined its national council. In 1945 she married and two years later gave birth to twins, but unfortunately died shortly afterwards.  Engineer of the Week No.107: Edith Mary Douglas (nee Dale) (13th November 1877 to 1963) On the 142nd anniversary of her birth we remember WES president Edith Douglas. Born in Cawnpore, India, where her father, George Desborough Dale, was in the Indian Civil Service. She was educated at home in England. Her marriage to Major Clifford Hugh Douglas in 1915 (his second, her only marriage) introduced her to engineering, financial and political matters, not least as he was a founder of the Social Credit Movement in the 1920s, on which he wrote and lectured widely. During the First World War her husband was an Assistant Superintendent of the Royal Aircraft Factory Farnborough, which gve Edith the unusual opportunity to be the first woman to fly in experimental bomber aircraft. When her husband became a co-director of the Swanwick Shipyard (Hamble River Yacht & Engineering Co.) on the River Hamble, she too became a director of the shipyard. Although she had no formal technical education, Edith was by no means a silent partner, but became fully involved in the technicalities of running the yard. During the Second World War of course the construction of yachts had to give way to Admiralty orders for small craft. It seems likely that she and her husband retired during or just after the war. Edith joined WES in 1932 and was President of the Society in 1938-9. She had a daughter and was also a keen sailing racer, golfer and lawn tennis competitor and died in 1963.  Engineer of the Week No.106: Joan Elizabeth Strothers (Lady Curran) (26 February 1916 – 10 February 1999) On our annual Remembrance Day, when we remember those who died in war, today we also remember Joan Curran, a woman whose invention helped to end the 2nd World War. Joan Strothers was a Welsh physicist-engineer who was the inventor of the UK form of the WW2 anti-radar measure known as ‘chaff’ or ‘window’. Born and educated in Swansea, where her father was an optician, Joan won a scholarship in 1934 to study physics at Newnham College, Cambridge. Although she gained an honours degree (1937) this was still 10 years before Cambridge actually awarded any degrees to women. She then won a government grant to study for a PhD in Philip Dee’s group at the Cavendish Laboratory at Cambridge, where she excelled at practical experimental work. The Second World War intervened and the PhD was abandoned in favour of the wartime needs. Dee took the group initially to the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough, only for their section to be immediately evacuated to the physics department at the University of Exeter. Joan was in a group with her future husband (Sam Curran) led by John Coles and working on the development of the proximity fuse. They were put into Leeson House (now a field studies centre) in Langton Matravers, Purbeck, which had become a top-secret radar research centre. Their successful design of a proximity fuse, was manufactured in the USA in time to become crucial in the fight against the V2 bombs later in the war. In 1940 Joan and Sam married and were both transferred to the Telecommunications Research Establishment (TRE) near Swanage, where Joan was assigned to the radar countermeasures group. It was here that Joan devised the technique that was codenamed Window (or Chaff), which consisted of strips of metal to fool the enemy radar. She tried various types of radar reflectors, including wires and sheets, before settling on strips of tin foil 1 to 2 centimetres wide and 25 centimetres long that could be scattered from bombers. This was first tried out during bombing raids on Hamburg, resulting in a much lower loss of Allied planes than usual. Another use was to imitate the radar reflections that would be detected from a phantom invasion force of ships in the Straits of Dover so as to distract the Axis forces as to where the D-Day landings really were. In his obituary of their mutual boss, Philip Dee, Sam said of this period: “When my wife (formerly Joan E. Strothers) was working at TRE on radar intelligence and countermeasures she carried out personally very early in 1942 the first experiment on ‘Window’ and this proved to be an experiment of truly major importance. I remember that at home she cut up a large amount of metal foil with her household scissors and then she organized the dropping of the thin metal foil strips from an aircraft sent up from Christchurch aerodrome. She had arranged that observation at the radar detection stations on the ground should be done. The effects on the radar screens were truly amazing and it looked as if a large fleet of aircraft was present. This first demonstration of ‘Window’ was cearly of outstanding importance to the whole of radar science.” Some WW2 historians believe that Joan Curran made an greater contribution to the Allies’ victory than her husband’s work did. Chaff is still in use today by the world’s armed forces, and its use military exercises often causes confusing images on weather forecasters’ radar. In 1944 both Joan and Sam were sent to the University of California, Berkeley, to work under the direction of Ernest Lawrence on the separation of isotopes of uranium as an important part of the Manhattan project (the development of the atomic bomb), following from their work (and joint publications) on nuclear physics at the Cavendish Laboratories. While they were in the USA Joan had the first of their children and her work in applied physics ended. After the war her husband worked first at the University of Glasgow and then became the first principal of the University of Strathclyde. Joan’s first child was severely disabled and she spent the rest of her life campaigning for the needs of the disabled, leading to her joining the local health board, special needs housing association and also established the Lady Curran Endowment fund for overseas students. Short entry for Twitter etc:  Engineer of the Week No.105: Elisa Leonida-Zamfirescu, Dipl. Ing., MAGIR (10 November 1887 – 25 November 1973) On her 132nd birthday we celebrate the life and work of Europe’s first female career engineer, Elisa Leonida-Zamfirescu. Elisa Leonida was one of the first formally-recognised female engineers in Europe. Due to prejudices against women in the sciences, she was rejected by the School of Bridges and Roads in Bucharest, Romania. However, in 1909, she was accepted at the Royal Academy of Technology in Berlin. She graduated from the university in 1912, with a degree in engineering, specialising in chemistry. Although other women graduated in engineering around this time, and Alice Perry 6 years earlier, Elisa stands out as a woman who had a full career as a chemical engineer specialising in mining geology. Born in the Romanian town of Galați, her father was an army officer but her grandfather and brother were both engineers. The Bucharest engineering school refused to admit her so she went to the Royal Academy of Technology Berlin, at Charlottenburg and then got her first job as an assistant at the Geological Institute of Romania. During World War 1 she ran a hospital and then married a chemist, Constantin Zamfirescu, with whom she had two daughters. After the war she returned to the Geological Institute, where she undertook field studies, including some that identified new resources of coal, shale, natural gas, chromium, bauxite and copper. She rose from assistant to the head of a group of 12 laboratories, investigating ore and water quality, and produced thousands of analytical reports, as well as published papers on bauxite and chromite. Other investigations included germanium content of coal and other ores and additives for mineral oils based on acrylic resins. Many of the national standards for analytical work which she drafted are still in use today. She also taught in a girls’s school and at the Bucharest School of Electricians and Mechanics. Elisa was the first female member of AGIR association of Romanian engineers but in later life she devoted a lot of her energy to campaigning against nuclear weapons. As well as various honours during her life, there is now a national prize for women in science and engineering, as well as a street in her birthplace, named after her. In 2018 she had a Google Doodle on her 131st birthday. Engineer of the Week No.103: Annabel Dott (nee Hall) (3 September 1868 - 5 November 1937)

On the 82nd anniversary of her death we commemorate the work of self-taught builder and electricity pioneer, Annabel Dott. Annabel Dott was a self-taught builder-developer, and an excellent self publicist as well as an Anglican vicar’s wife. Born in Stepney in 1868 and raised in Hackney as the single child of her widowed mother. She spent her thirties in Bournemouth nursing her ailing mother. When her mother died Annabel departed for South Africa where she married William Patrick Dott. It was in Woodstock, Cape Town, that she had her first experiences of working on a number buildings supervising the modification and repairs: remodelling the sadly neglected rectory; restoring The Treaty House; renovating school rooms. She later reported how much this had taught her about the processes of building - learning by trial and error - and of supervising workmen. That she valued her workers is indicated by the fact that she claimed it was important to pay them above union rates, that it was important to listen to them and that in at least two of her schemes she made presentations to a key member of her building team. On her return to England in 1909 during an enforced period of convalescence following a still birth Annabel studied as if preparing for a Clerk of Works exam and then considered herself ready to undertake her first building project in this country. In the moorland village of Goathland, Yorkshire, she designed nine cottages intended initially as holiday lets and also an impressive detached house for herself and her husband. In 1917 the cottages, with some alterations, were made over to a charitable company for the use of disabled officers of the war. A period in Dorset near the army camp of Blandford, where Patrick was a chaplain, gave her the opportunity to write several significant articles (in The Nineteenth Century and The Architectural Review) about her work. The end of the war brought Patrick’s appointment to a parish in south London and Annabel’s energies were directed at new projects. This period as she entered her fifties was perhaps the busiest of her life. In south Croydon she had a number of building projects - improvements to the vicarage, the building of a parish room, renovations to an old manor house and some conversions of a couple of large houses into flats for professional women. She was also involved for a brief time with the establishment of Women’s Pioneer Housing, an organisation providing small flats for single women of moderate means in West London. Annabel also conceived her second and perhaps most significant project, an imaginative settlement of houses in East Sussex. At a distance of some 40 miles from the vicarage, she supervised the building of seventeen properties in 50 acres of woodland at Grey Wood, East Hoathly. A group of nine were designed around a quadrangle and had shared facilities which were run on electricity generated in a powerhouse which she had built. She wanted to provide for a community, but one in which the inhabitants did not feel forced into each others company. There were laundry facilities, a washer up (dish washer) and bakehouse together with some guest rooms and a flat. The houses had electric light, electric kettles and irons. She also paid a lot of attention to the outside environment, providing an extensive garden area and planting fruit trees and bulbs in the woods. There was a small lake created from damning a local stream; its water was important for the power house but it was also described as a boating lake. Elsewhere in the woods were three pairs of semi detached houses and one small detached house. During the building period as at other times in her life Annabel was again unwell, at one point describing that she had been brought to the site on a stretcher to supervise the building work. The houses were originally let out but after only a few years Annabel was anxious to sell the estate as a whole or in part. This might eventually have happened in about 1930. It is still unclear how her housing projects were funded although there is evidence of mortgages taken out and redeemed, and the grand detached house in Goathland was sold to a member of the Rowntrees’ family in 1920. It should be remembered that vicars of this period did not always have adequate incomes from their stipend and later from their pensions, and that they may have undertaken other work or devised entrepreneurial schemes in order to supplement their income. This could be what Annabel had in mind when she first built the houses in Yorkshire. Annabel’s final realised scheme was the design and building of a church hall for the parish church of St Mary’s, Barnes, to which she and Patrick had moved in 1923. Now known as Kitson Hall it has some trade mark Annabel features including stone mullioned windows and a covered verandah or stoep. The hall was opened in 1928. For the ensuing years Annabel and her husband continued their life in the parish community of Barnes. After a flurry of activity writing articles promoting her houses and the labour-saving value of the use of electricity, and then selling Grey Wood, Annabel and Patrick seemed to have settled into a quieter more conventional life at Barnes until that is there was a bit of a local furore about Patrick’s proposal to build flats on the rectory grounds. In this he was supported by Annabel, although the plans do not seem to have been hers, and at the resultant public enquiry evidence in support of the scheme was given by a high profile planner, Professor Adshead. The strain of the local bad feeling about the scheme as well as their continuing poor health may have led Patrick to organise a move to a quieter parish. The last years of their life must have been spent in some distress Their new rectory at Winterslow was large and in a terrible state of repair. Annabel drew up a scheme for a new smaller rectory literally writing letters from her sick bed - she had had a heart attack - badgering the church authorities for approval. She died with this final scheme still unfulfilled and is buried with Patrick who died the following year, in the churchyard there. However, her three significant schemes live on together with the small parish room in Croydon. The houses in both Yorkshire and Sussex are delightful places in which to live and the church halls are well used and appreciated by the congregations. Annabel considered herself a master builder rather than a woman architect. She undoubtedly developed a range of skills and knowledge through practical experience and studying in the fields of construction, design, and technology. These, in combination with determination, forceful communication skills and some visionary ideas, meant that she achieved much in a realm not easily accessible to women of her time. [Thanks to guest author, Lynne Dixon, for the text and images for this interesting woman] |

- Home

- Electric Dreams

- All Electric House, Bristol

- Top 100 Women

- Engineer of the Week

- The Women

- Timeline

- WES History

- EAW

- Teatowels For Sale

- 50 Women in Engineering

- Museum Trails

- Waterloo Bridge

- History Links

- Blue Plaques

- Virtual Blue Plaques

- Career and Inspiration Links

- Contact

- Outreach

- Photo Gallery

- Bluestockings and Ladders