Engineer of the Week No.114: Catherine Anselm ‘Kate’ Gleason, MASME (25 November 1865 – 9 January 1933) In the week of her 154th birthday we remember the USA’s first woman engineer, “Concrete Kate” Gleason, mechanical engineer and house builder. Kate Gleason, although one of the first women admitted to ASME (1918) and the first to be admitted to Cornell (1884) to study engineering, never completed an engineering degree. Much of her engineering was learned the practical way, from childhood work in her father’s factory, Gleason Works, which specialised in gear-cutting machines. After many years helping her father’s firm, latterly as a salesperson, in 1914 she left to take up an appointment as receiver of bankruptcy for the Ingle Machine Company. She is believed to have been the first woman to take on such a role, but the first woman to do so. She was able to turn the company around, repay its debts and return it to its stockholders within a year. From this success she moved on to building factories and housing in the East Rochester (New York state) area. She worked with local architects to design low cost housing using her own ideas for poured concrete construction, materials selection, and site management. Taking a lesson in the producton methods of the big automobile factories which she had visited selling her father’s machines, her sites were run more like Ford’s production lines, with every worker only having exactly those materials required for the immediate piece of work. The houses were in a Dutch style set in a garden suburb layout. Her concrete houses led to her becoming the first female member of the American Concrete Institute. She also built some houses in Sausalito, California and at her winter home in Beaufort, South Carolina where she had plans to make a community of garden apartments for artists. However only 10 of these were completed at the time of her death, in 1933, from pneumonia. She never married, considering marriage an impediment to her professional interests. Her summer home, the island of Dataw, she left to her secretary. She seems to have had a couple of patents but not to have made much commercial use of them. The University of South Carolina’s archives hold 2 home movies made by Kate, unfortunately none of the shots include any of her professional work.

0 Comments

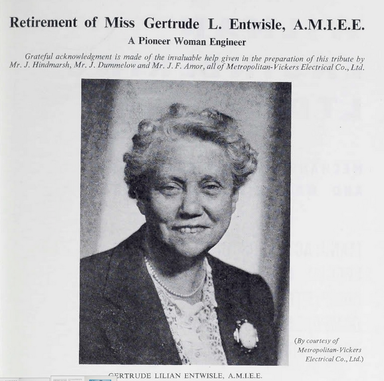

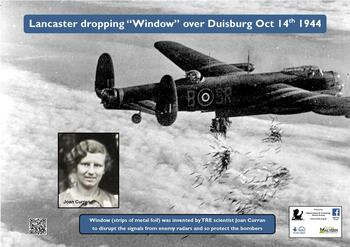

Engineer of the Week No.113: Beryl Catherine Platt, Baroness Platt of Writtle CBE DL FRSA FREng HonFIMechE (née Myatt) (18 April 1923 – 1 February 2015) As WES nears the end of its Centenary Year we remember the work of Beryl Platt who helped establish the Women Into Science and Engineering Year in 1984. Baroness Beryl Platt was of the generation of women for whom the Second World War opened up a brief window of opportunity in engineering, only for the ‘marriage bar’ to shut it again. Her mathematical talent took her from Westcliff High School for Girls to Girton College Cambridge, where she was only the 9th woman ever to pass the mechanical science tripos with honours (1943) under the wartime accelerated degree programme. Cambridge of course did not at that time actually award the degrees which women had earned. The same programme directed her into aeronautical engineering at Hawker Aircraft Ltd, as a technical assistant in the experimental flight section of the Design Office. Her work analysed data from test flights of fighter planes, including the Hurricane, work which she later recalled as “I couldn’t ever let anyone down. We were testing and producing fighters which really made a difference to winning the war”. In 1946 she became a technical assistant in the performance and analysis section of British European Airways’ Project Department, testing new aircraft and ensuring compliance with UK and international safety regulations. However, in 1949 she married and the convention of those times was that married women retired from their paid employment. This, though, was the start of her long and productive political career from parish councillor, via the county council, to becoming an active Conservative peer in the House of Lords and chair of the Equal Opportunities Commission. Although her own career as an engineer had been brief, she made it her business to do much to support the opportunities for women in engineering. Her work setting up the Women Into Science and Engineering Year in 1984 and its subsequent programmes for girls and women, included rejoining the Women’s Engineering Society and serving on numerous engineering education related boards. Her eminent career in support of equal opportunities for women and technical engineering education led to many honorary doctorates, the CBE in 1978 and the Freedom of the City of London in 1988.  Engineer of the Week No.112: Elizabeth (Betty) Laverick (nee Rayner) OBE, FIEE, CEng, FInstP, SMIRE, HonFUMIST (25th November 1925 – 12th January 2010) On what would have been her 94th birthday we remember electronics engineer, Betty Laverick. Elizabeth Laverick was born in Amersham, Buckinghamshire, in 1925, into a family of second-generation chemists, her father, William Rayner, being a manufacturing chemist. Her mother Alice Maria Garland assisted with the administration of the business. She won scholarship to Dr Challoner’s Grammer School nearby, then a co-educational school, where she became the only girld in the Higher Schools Certificate class. She and her older sister were both strongly encouraged by their parents to go to University but Elizabeth’s November birthday meant Durham could not take her until 1943. She spent that year as a scientific civil servant at the Radio Research Station near Slough, as a Technical Assistant, Grade III. She graduated from Durham in 1946 with a degree in Physics and Radio (a special wartime course) and stayed onto to a PhD on “ Dielectric measurements at audio frequencies using a differential”. She married a fellow student, Charles Laverick in 1946 and in 1951 they were both hired by GEC Stanmore (Marconi Defence Systems Ltd.) where she worked as a microwave engineer, working on guided weapons systems. In 1954 Laverick moved to Elliott Automation (part of Elliot Brothers) as a microwave engineer, gaining commercial experience in microwave instruments and rising to become the general manager of Elliott Automation Radar Systems. She published papers on some of her work and was involved in the development of the airborne Early Warning system later known as the Nimrod. In 1971 she moved away from practical engineering to become the first female deputy secretary of the Institute of Electrical Engineers, which gave her the opportunity to pursue her interests in applying her management expertise to the Institution’s career development for members. In her reitrement in 1985 Laverick joined the Court of City University, as well as doing some work as a consultant in advanced manufacturing in electronics Having joined the Women’s Engineering Society in the late 1950s, meet other women engineers and promote the career to girls, she soon joined the London Branch committee and the national council and became the society’s president in 1968/69. She continued her active involvement as Honorary Treasurer and was editor of the journal for 7 years. As well as her OBE in 1993 she was also honoured with an honorary fellowship at UMIST and became a liveryman of the Worshipful Company of Engineers,. Her leisure interests included tapestry and music and she became interested in nursing homes for the elderly, eventually selling the family home in Amersham for that purpose. She married again shortly before she died, to Peter, her long time companion. She died in 2010.  Engineer of the Week No. 111: Jean Marion Taylor, BSc, FIWSc (29th February 1924-18th 1999) Today we remember Jean Taylor, for her work the timber preservation industry. Jean Taylor was generally described in her lifetime as an entomologist but, although that was the source of her expertise, perhaps today she might be considered to have been an applied biologist or bio-engineer. It remains commonplace to think of engineering as only being about the use of metals, and perhaps concrete, but wood is just as much an engineering material, requiring the same engineering mode of thought, in order to use it effectively, which she was certainly doing in her work. Jean was born, on a Leap Day, into a modest background in Cardiff, Wales, where her father was a tobacconist and she had two younger siblings. She served in the WAAF during WW2, working on air-frame maintenance and becoming a skilled fitter. After the war she went to Cardiff University and gained a degree in zoology, which took her to her first job, in the Entomology Section of the government’s Forest Products Research Laboratory in 1949 to work for Dr. R.C. Fisher. Her work was on the prevention and control of wood-boring insect infestation. She led the evaluation of the newer generation of insecticides and was particularly concerned with the development of laboratory testing technology and how to apply laboratory results to industry. Her expertise led to involvement in drafting international standards with the European Standards Organisation, CEN, and in the International Research Group on Wood Preservation, and collaborations with colleagues in Australia. She published about 14 papers on various aspects of wood preservation from 1960-1991. After 20 years at the FPRL she moved into industry, becoming the technical director at Protim Ltd., where one aspect of her work was the investigation of insect resistance of wood and plastic composites. From becoming the Institute of Wood Sciences’ first female fellow in 1962, she was active in the organisation, on many committees, setting up its newsletter and becoming its president in 1986-88 Colleagues remembered her not only for her exacting attitude to her work but her skill in explaining its complexities in a very clear and engaging way. Jean was also an active golfer and member of the local branch of the Soroptimists, whose secretary and branch president she was for several years.  Engineer of the Week No.110: Peggy Lilian Hodges (11th June 1921 – 21st November 2008) OBE, MA, CEng, FRAeS, FIMA, HonFIET On the 11th anniversary of her death we remember defence electronics engineer Peggy Hodges. Peggy Lilian Hodges, was born in London in 1921 into modest circumstances which cannot have improved when her father Ernest, a credit draper, died when she was only 4 years old. She was educated at the Westcliff High School for Girls, in Essex and then gained a modest State Scholarship to take a degree in mathematics from Girton College, Cambridge in 1943. Her first job was as a radio engineer with Standard Telephone & Cable, where she worked on airborne communications and the ILS blind beacon landing equipment. In 1950 she joined the GEC Applied Electronics Laboratories at Stanmore, Middlesex, as a microwave and systems engineer, working on guided weapons. Missile projects included Red Dean and Sea Dart, which relied heavily on the systems assessments produced by Hodges and her team. She became an expert on simulation and systems, including assessments of random aberrations, types of dish stabilisation, target glint and sea reflection problems. She progressed to become Systems Manager and then Project Manager of the Guided Weapons Project (Sea Dart Guidance) in the Guided Weapons Division. She was consulted by other laboratories and government departments and was sent on government missions to the USA. She was a member of the Radome Electrical Performance Panel for Guided Weapons and aircraft for the Ministry of Aviation. Among other projects, Hodges worked in the Underwater Weapons Division on trials planning and analysis for air-launched guided torpedoes, and later worked on simulation, identifying problems affecting guided weapons systems. Her work on guided weapons was featured in a BBC documentary in the 1960s, when she was filmed at work at the Ministry of Defence’s guided-missile firing range at Aberporth in Wales. In 1971 she was promoted to Deputy guided weapons project division manager (systems) at Marconi space and defence systems, within GEC. Her division did general performance work, systems studies, simulations, trials planning analysis. Hodges formally retired from GEC in 1981 but continued to do general systems consultancy for the Guided Weapons Division of Marconi Space and Defence Systems (MSDS), Stanmore. In retirement she did voluntary work in an old people’s home, and was involved in the setting up, by the Institution of Electrical and Electronics Incorporated Engineers, of a new annual competition: the Girl Technician Engineer of the Year, later Young Woman Engineer of the Year. She was Chair of the Caroline Haslett Trust set up to encourage girls, by means of scholarships and competitions, to take up careers in engineering, and in 1982-3 was President of Soroptimist International St Albans and District. She was also a member of the Fawcett Society, was interested in ballet, opera and classical music. Having joined the Women’s Engineering Society in 1960 she soon became a council member and was the society’s president in 1972-3 In 1959 she became an Associate Fellow of the Royal Aeronautical Society and a full Fellow 10 years later, having already been the first woman to take the Chair at a meeting of the Royal Aeronautical Society, when the subject under discussion was "Guided Weapon Simulators." In 1970 she received the Whitney-Straight Award for outstanding performance by a woman in the field of Aeronautics, and 2 years later she was awarded the OBE in the Queen’s Birthday Honours, for her contribution to guided weapons technology. In 1994 Hodges became the first female honorary fellow of Institution of Electronics and Electrical Incorporated Engineers (IEEIE, later the IET). She died in 2008 in Buckinghamshire and legacies include the “Peggy Hodges Prize” for the highest performing female student completing the second year of a full time MEng/BEng Engineering degree at the University of Hertfordshire.  Engineer of the Week No.109: Gertrude Lillian Entwisle BSc, AMIEE (1892 -18th November 1961) On the 58th anniversary of her death, today we remember electrical engineer Gertrude Entwisle. A Lancashire lass, Gertrude was educated at Milham Ford School, Oxford and then at Manchester High School For Girls, where she was awarded an Exhibition to enable her to attend Manchester University to study physics. She was one of the first women to attend engineering lectures at the University, after the engineering faculty decided to open its classes to women mid-way through her physics degree. She was the first woman to be admitted to the technical staff of British Westinghouse, the first woman member of the Society of Technical Engineers and the first Student, Graduate and Associate Member of the IEE (now the IET). She owned a threewheel Harper Runabout – acurious blend of motor-trike and small car. She worked mainly on the design of DC motors and generators until 1923 when she spent about 20 years working on AC before returning to DC motors during the Second World War. One of her largest designs was the DC motor for a motor generator flywheel set on the winding gear at Broken Hill mines in Australia. Towards the end of her career she became a specialist in large exciters for coal and hydropower stations. An early member of WES, she became Vice President in 1937 but yielded the presidency for 1938 to Caroline Haslett so that the latter could be president during the society’s 21st birthday year, but was then president for 1942. She retired from Metropolitan-Vickers in 1954, after a 39-year career, and died in 1961.  Engineer of the Week No.108: Pauline Mary de Peauly Gower MBE (Mrs Fahie) (22 July 1910 - 2 March 1947) In Remembrance Week we remember Pauline Gower who set up and commanded the women’s Air Transport Auxiliary, in WW2 Pauline Gower, although from a privileged background, had to find her own way in her chosen career as a pilot, due to family opposition. She supported herself giving music lessons, in order to take her first flying lessons, gaining her A licence (private pilot) in 1930 and the following year got her B licence (commercial pilot) after lessons at the London aeroplane club, Stag Lane. This was where she met Dorothy Spicer with whom she went on to set up a commercial flying company, with a Gypsy Moth plane. Whilst Pauline went on to get every possible pilot’s qualifications, Dorothy did likewise in the aero-engineering side. However the business was short-lived and they went to join various air-display teams which were popular at the time. In 1938 she was invited to become a member of the Gorrell committee on aircraft safety. As the Second World War approached, Pauline campaigned for women pilots to be allowed to do their bit. In 1939 she was appointed a commissioner of the Civil Air Guard. Later that year she was appointed as an Air Transport Auxiliary second officer and given the job of forming a women's section. The number of women pilots rose to 150, with a few flight engineers too, and they eventually flew all types of aircraft, from light trainers to four-engined bombers. Some of ‘her girls’ even gave their lives, including the most famous of all, her friend Amy Johnston. Pauline campaigned for and finally obtained the same pay for her women pilots as the men received for doing the same work, and was awarded an MBE in 1942. Her exceptional leadership skills led to her appointment as a director of British Overseas Airways, the first woman in such a senior position in any national airline. Pauline joined the Air Section of the Women’s Engineering Society in 1931, and was an active member, speaking, writing articles for The Woman Engineer and promoting flying careers to members. In 1935 she joined its national council. In 1945 she married and two years later gave birth to twins, but unfortunately died shortly afterwards.  Engineer of the Week No.107: Edith Mary Douglas (nee Dale) (13th November 1877 to 1963) On the 142nd anniversary of her birth we remember WES president Edith Douglas. Born in Cawnpore, India, where her father, George Desborough Dale, was in the Indian Civil Service. She was educated at home in England. Her marriage to Major Clifford Hugh Douglas in 1915 (his second, her only marriage) introduced her to engineering, financial and political matters, not least as he was a founder of the Social Credit Movement in the 1920s, on which he wrote and lectured widely. During the First World War her husband was an Assistant Superintendent of the Royal Aircraft Factory Farnborough, which gve Edith the unusual opportunity to be the first woman to fly in experimental bomber aircraft. When her husband became a co-director of the Swanwick Shipyard (Hamble River Yacht & Engineering Co.) on the River Hamble, she too became a director of the shipyard. Although she had no formal technical education, Edith was by no means a silent partner, but became fully involved in the technicalities of running the yard. During the Second World War of course the construction of yachts had to give way to Admiralty orders for small craft. It seems likely that she and her husband retired during or just after the war. Edith joined WES in 1932 and was President of the Society in 1938-9. She had a daughter and was also a keen sailing racer, golfer and lawn tennis competitor and died in 1963.  Engineer of the Week No.106: Joan Elizabeth Strothers (Lady Curran) (26 February 1916 – 10 February 1999) On our annual Remembrance Day, when we remember those who died in war, today we also remember Joan Curran, a woman whose invention helped to end the 2nd World War. Joan Strothers was a Welsh physicist-engineer who was the inventor of the UK form of the WW2 anti-radar measure known as ‘chaff’ or ‘window’. Born and educated in Swansea, where her father was an optician, Joan won a scholarship in 1934 to study physics at Newnham College, Cambridge. Although she gained an honours degree (1937) this was still 10 years before Cambridge actually awarded any degrees to women. She then won a government grant to study for a PhD in Philip Dee’s group at the Cavendish Laboratory at Cambridge, where she excelled at practical experimental work. The Second World War intervened and the PhD was abandoned in favour of the wartime needs. Dee took the group initially to the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough, only for their section to be immediately evacuated to the physics department at the University of Exeter. Joan was in a group with her future husband (Sam Curran) led by John Coles and working on the development of the proximity fuse. They were put into Leeson House (now a field studies centre) in Langton Matravers, Purbeck, which had become a top-secret radar research centre. Their successful design of a proximity fuse, was manufactured in the USA in time to become crucial in the fight against the V2 bombs later in the war. In 1940 Joan and Sam married and were both transferred to the Telecommunications Research Establishment (TRE) near Swanage, where Joan was assigned to the radar countermeasures group. It was here that Joan devised the technique that was codenamed Window (or Chaff), which consisted of strips of metal to fool the enemy radar. She tried various types of radar reflectors, including wires and sheets, before settling on strips of tin foil 1 to 2 centimetres wide and 25 centimetres long that could be scattered from bombers. This was first tried out during bombing raids on Hamburg, resulting in a much lower loss of Allied planes than usual. Another use was to imitate the radar reflections that would be detected from a phantom invasion force of ships in the Straits of Dover so as to distract the Axis forces as to where the D-Day landings really were. In his obituary of their mutual boss, Philip Dee, Sam said of this period: “When my wife (formerly Joan E. Strothers) was working at TRE on radar intelligence and countermeasures she carried out personally very early in 1942 the first experiment on ‘Window’ and this proved to be an experiment of truly major importance. I remember that at home she cut up a large amount of metal foil with her household scissors and then she organized the dropping of the thin metal foil strips from an aircraft sent up from Christchurch aerodrome. She had arranged that observation at the radar detection stations on the ground should be done. The effects on the radar screens were truly amazing and it looked as if a large fleet of aircraft was present. This first demonstration of ‘Window’ was cearly of outstanding importance to the whole of radar science.” Some WW2 historians believe that Joan Curran made an greater contribution to the Allies’ victory than her husband’s work did. Chaff is still in use today by the world’s armed forces, and its use military exercises often causes confusing images on weather forecasters’ radar. In 1944 both Joan and Sam were sent to the University of California, Berkeley, to work under the direction of Ernest Lawrence on the separation of isotopes of uranium as an important part of the Manhattan project (the development of the atomic bomb), following from their work (and joint publications) on nuclear physics at the Cavendish Laboratories. While they were in the USA Joan had the first of their children and her work in applied physics ended. After the war her husband worked first at the University of Glasgow and then became the first principal of the University of Strathclyde. Joan’s first child was severely disabled and she spent the rest of her life campaigning for the needs of the disabled, leading to her joining the local health board, special needs housing association and also established the Lady Curran Endowment fund for overseas students. Short entry for Twitter etc:  Engineer of the Week No.105: Elisa Leonida-Zamfirescu, Dipl. Ing., MAGIR (10 November 1887 – 25 November 1973) On her 132nd birthday we celebrate the life and work of Europe’s first female career engineer, Elisa Leonida-Zamfirescu. Elisa Leonida was one of the first formally-recognised female engineers in Europe. Due to prejudices against women in the sciences, she was rejected by the School of Bridges and Roads in Bucharest, Romania. However, in 1909, she was accepted at the Royal Academy of Technology in Berlin. She graduated from the university in 1912, with a degree in engineering, specialising in chemistry. Although other women graduated in engineering around this time, and Alice Perry 6 years earlier, Elisa stands out as a woman who had a full career as a chemical engineer specialising in mining geology. Born in the Romanian town of Galați, her father was an army officer but her grandfather and brother were both engineers. The Bucharest engineering school refused to admit her so she went to the Royal Academy of Technology Berlin, at Charlottenburg and then got her first job as an assistant at the Geological Institute of Romania. During World War 1 she ran a hospital and then married a chemist, Constantin Zamfirescu, with whom she had two daughters. After the war she returned to the Geological Institute, where she undertook field studies, including some that identified new resources of coal, shale, natural gas, chromium, bauxite and copper. She rose from assistant to the head of a group of 12 laboratories, investigating ore and water quality, and produced thousands of analytical reports, as well as published papers on bauxite and chromite. Other investigations included germanium content of coal and other ores and additives for mineral oils based on acrylic resins. Many of the national standards for analytical work which she drafted are still in use today. She also taught in a girls’s school and at the Bucharest School of Electricians and Mechanics. Elisa was the first female member of AGIR association of Romanian engineers but in later life she devoted a lot of her energy to campaigning against nuclear weapons. As well as various honours during her life, there is now a national prize for women in science and engineering, as well as a street in her birthplace, named after her. In 2018 she had a Google Doodle on her 131st birthday. Engineer of the Week No.103: Annabel Dott (nee Hall) (3 September 1868 - 5 November 1937)

On the 82nd anniversary of her death we commemorate the work of self-taught builder and electricity pioneer, Annabel Dott. Annabel Dott was a self-taught builder-developer, and an excellent self publicist as well as an Anglican vicar’s wife. Born in Stepney in 1868 and raised in Hackney as the single child of her widowed mother. She spent her thirties in Bournemouth nursing her ailing mother. When her mother died Annabel departed for South Africa where she married William Patrick Dott. It was in Woodstock, Cape Town, that she had her first experiences of working on a number buildings supervising the modification and repairs: remodelling the sadly neglected rectory; restoring The Treaty House; renovating school rooms. She later reported how much this had taught her about the processes of building - learning by trial and error - and of supervising workmen. That she valued her workers is indicated by the fact that she claimed it was important to pay them above union rates, that it was important to listen to them and that in at least two of her schemes she made presentations to a key member of her building team. On her return to England in 1909 during an enforced period of convalescence following a still birth Annabel studied as if preparing for a Clerk of Works exam and then considered herself ready to undertake her first building project in this country. In the moorland village of Goathland, Yorkshire, she designed nine cottages intended initially as holiday lets and also an impressive detached house for herself and her husband. In 1917 the cottages, with some alterations, were made over to a charitable company for the use of disabled officers of the war. A period in Dorset near the army camp of Blandford, where Patrick was a chaplain, gave her the opportunity to write several significant articles (in The Nineteenth Century and The Architectural Review) about her work. The end of the war brought Patrick’s appointment to a parish in south London and Annabel’s energies were directed at new projects. This period as she entered her fifties was perhaps the busiest of her life. In south Croydon she had a number of building projects - improvements to the vicarage, the building of a parish room, renovations to an old manor house and some conversions of a couple of large houses into flats for professional women. She was also involved for a brief time with the establishment of Women’s Pioneer Housing, an organisation providing small flats for single women of moderate means in West London. Annabel also conceived her second and perhaps most significant project, an imaginative settlement of houses in East Sussex. At a distance of some 40 miles from the vicarage, she supervised the building of seventeen properties in 50 acres of woodland at Grey Wood, East Hoathly. A group of nine were designed around a quadrangle and had shared facilities which were run on electricity generated in a powerhouse which she had built. She wanted to provide for a community, but one in which the inhabitants did not feel forced into each others company. There were laundry facilities, a washer up (dish washer) and bakehouse together with some guest rooms and a flat. The houses had electric light, electric kettles and irons. She also paid a lot of attention to the outside environment, providing an extensive garden area and planting fruit trees and bulbs in the woods. There was a small lake created from damning a local stream; its water was important for the power house but it was also described as a boating lake. Elsewhere in the woods were three pairs of semi detached houses and one small detached house. During the building period as at other times in her life Annabel was again unwell, at one point describing that she had been brought to the site on a stretcher to supervise the building work. The houses were originally let out but after only a few years Annabel was anxious to sell the estate as a whole or in part. This might eventually have happened in about 1930. It is still unclear how her housing projects were funded although there is evidence of mortgages taken out and redeemed, and the grand detached house in Goathland was sold to a member of the Rowntrees’ family in 1920. It should be remembered that vicars of this period did not always have adequate incomes from their stipend and later from their pensions, and that they may have undertaken other work or devised entrepreneurial schemes in order to supplement their income. This could be what Annabel had in mind when she first built the houses in Yorkshire. Annabel’s final realised scheme was the design and building of a church hall for the parish church of St Mary’s, Barnes, to which she and Patrick had moved in 1923. Now known as Kitson Hall it has some trade mark Annabel features including stone mullioned windows and a covered verandah or stoep. The hall was opened in 1928. For the ensuing years Annabel and her husband continued their life in the parish community of Barnes. After a flurry of activity writing articles promoting her houses and the labour-saving value of the use of electricity, and then selling Grey Wood, Annabel and Patrick seemed to have settled into a quieter more conventional life at Barnes until that is there was a bit of a local furore about Patrick’s proposal to build flats on the rectory grounds. In this he was supported by Annabel, although the plans do not seem to have been hers, and at the resultant public enquiry evidence in support of the scheme was given by a high profile planner, Professor Adshead. The strain of the local bad feeling about the scheme as well as their continuing poor health may have led Patrick to organise a move to a quieter parish. The last years of their life must have been spent in some distress Their new rectory at Winterslow was large and in a terrible state of repair. Annabel drew up a scheme for a new smaller rectory literally writing letters from her sick bed - she had had a heart attack - badgering the church authorities for approval. She died with this final scheme still unfulfilled and is buried with Patrick who died the following year, in the churchyard there. However, her three significant schemes live on together with the small parish room in Croydon. The houses in both Yorkshire and Sussex are delightful places in which to live and the church halls are well used and appreciated by the congregations. Annabel considered herself a master builder rather than a woman architect. She undoubtedly developed a range of skills and knowledge through practical experience and studying in the fields of construction, design, and technology. These, in combination with determination, forceful communication skills and some visionary ideas, meant that she achieved much in a realm not easily accessible to women of her time. [Thanks to guest author, Lynne Dixon, for the text and images for this interesting woman]  Engineer of the Week No.102: Ilse ter Meer (nee Knott), Dipl. Ing., (14 October 1899 – 3 November 1996) On the 23rd anniversary of her death we remember the work of mechanical engineer, Ilse ter Meer. Ilse ter Meer was born in Hanover into an engineering family: her father Gustav was an engineer and director of Hanomag, designing waste water centrifuges. She studied mechanical engineering at the Technical University in Hanover (1919-1922), and then at the Technical University in Munich (1922-24), with another pioneer female engineer Wilhelmine Vogler, in the face of overt hostility from the male students. On graduating she married engineer Carl Knott. She set up her own consultancy in Aachen and worked on her father’s patented centrifuges (Schlammtrocknungs GMBH). In 1925 she became the first woman member of Verein Deutscher Ingenieure (VDI). She worked for various factories in Hanover and Dresden and in the Danzig shipyards and later worked for Siemens & Halske in Berlin. In 1929 became the Women’s Engineersing Society’s (WES) first German member. On the occasion of the World Power Conference in 1930 in Berlin, she organized the first meeting of German female engineers. However, her negative aspects cannot be ignored: she continued to work at Siemens & Halske through the Nazi era. This company was heavily involved in armaments production during the Second World War, including the use of forced/slave labour and inmates of the women's concentration camp Ravensbrück. After the war she resumed contact and active membership of WES and, in 1960, she was one of the six founders of the VDI committee for its women members – in 1975 she was awarded the VDI gold medal for her 50 years’ of membership. From 1956 she headed the office of the general agency of an American electrical appliance manufacturer. Despite her wartime association with the Nazis, she has been honoured with a street in Hanover: Ilse ter-Meer-Weg, and an auditorium at TU Munich is named after her. Leibniz University also awards an Ilse ter Meer book prize (Euros 5,000) for a book which promotes equal opportunities, family friendliness or diversity. |

- Home

- Electric Dreams

- All Electric House, Bristol

- Top 100 Women

- Engineer of the Week

- The Women

- Timeline

- WES History

- EAW

- Teatowels For Sale

- 50 Women in Engineering

- Museum Trails

- Waterloo Bridge

- History Links

- Blue Plaques

- Virtual Blue Plaques

- Career and Inspiration Links

- Contact

- Outreach

- Photo Gallery

- Bluestockings and Ladders