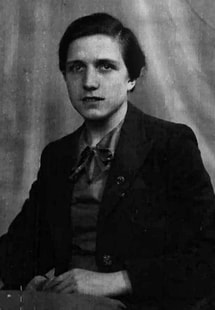

Engineer of the Week No.101: Irene Joy Ferguson, later Jonathan Ferguson, ARAeSoc (30th October 1915 - 31st May 1974) On what would have been his 104th birthday we remember Jonathan Ferguson, pilot and technical civil servant. Jonathan Ferguson, pilot and scientific civil servant, was born Irene Joy Ferguson on 30th October 1915, Wellington Street, Lurgan, Co Armagh, Ireland (now Northern Ireland). Her father was Edward Ferguson (1880-1947), a boot salesman, and her mother was Jessie Robertson Fyfe (died 1950). Ferguson had gender reassignment surgery in 1958 and lived the remainder of his life as a man, until his death in 1974. [For convenience of the narrative I will use the female pronouns for the part of Ferguson’s life when she lived as a woman, i.e. from 1915-58, and male pronouns from that point onwards. I am advised that it is nowadays the convention to use the gender pronouns of the gender to which a person has been reassigned but in this biography I feel this would make for a confused story and clumsy syntax. No disrespect is meant towards Ferguson’s ultimate gender choice.] She was educated at Lurgan High School and Lurgan College. She became a “Lady Demonstrator” in Electricity Board showrooms, first in Northern Ireland and then in the South of England, whilst studying electrical engineering part time, probably at local technical colleges. Having won a public speaking competition organised by the British Electrical Development Association, she was introduced to Caroline Haslett who mentored her and helped her to find a job in the switchgear sales department at British Thompson-Houston, from which she was able to become a Technical Assistant TA2, under the Director of Technical Development, Ministry of Aircraft Production until she joined the ATA in 1943. Although her employment records indicate that she did not have a degree, the grade she later reached in the scientific civil service were normally only open to graduates. Also, on entry to the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA), she was noted as having a much greater technical background than their usual new entry pilots, most of whom had a great deal more flight experience than she did. She joined the volunteer Civil Air Guard and obtained her private pilot’s licence. She entered the ATA as a Third Officer and was promoted to Second Officer in January 1944. Joy was posted to a number of different Ferry Pools (FPs). Of these she spent the most aggregate time at No.15 FP, at Hamble. Hamble was one of only two Fps which were all-women, the others being mixed. Joy was not the most natural of pilots, for all her enthusiasm, and had to resit some of her practical flying tests, and remained at the Class 3 level, flying 26 different sorts of aircraft. In October 1945 Joy was demobilised from the ATA and returned to her work as a scientific civil servant in the Ministry of Supply. It is not clear what her role was but may have been related to the production of Pilot Notes, the handbooks for new aircraft, which the ATA pioneered in their need to provide clear summaries of what pilots needed to know to fly a new aircraft quickly. She moved back to live in north London and 1948 Ferguson became an associate member of the Royal Aeronautical Society. At this time Joy had a commission as a Pilot Officer in the WRAFVR from 1949-54, acted as an advisor to the Girl Guides’ Air Rangers section for older girls and took an active interest in the complexities of the mathematics required for setting the handicaps for air races. She was active in the Women’s Engineering Society from 1947-57 and gave a talk on the handicapping maths to the London WES group in 1952. In 1958 Ferguson announced publicly that he would be living as Jonathan, rather than Joy, following what in those days was referred to as “sex change” but which we now call “gender reassignnment” surgery. Interestingly, one of Ferguson’s ATA friends said that she had been told as early as 1939 that such surgery would have been possible then but decided to postpone it until after the war on the reasonable premise that she could serve her country just as well as a woman as a man. The change to living as a man resulted in worldwide press reports of this, stating that Ferguson’s civil service employers were unconcerned about the change and that he would continue with his work as before, but with an increase in pay to the male grade. That she joined the Ministry of Supply in a technical role during the war would be unremarkable at a time when many women found such doors opening in the desperate need to release men for the front line. It is more remarkable however that she not only returned to that work after the war, when there was a very considerable social and legislative drive to force women out of their wartime technical work and back into the domestic sphere, but also remained and prospered into the higher ranks of the scientific civil service. She must have been doing valued work to achieve that and also to gain the unstinted support of her bosses when the time came to come out and become Jonathan. We may never know the full story of what Jonathan’s work contributed to the development of aviation in the UK, but I think we can be sure that it held significance at the time.

2 Comments

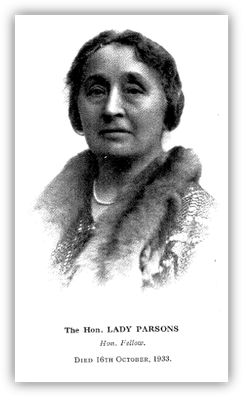

Engineer of the Week No.100: Marion Katharine Petch McQuillan BSc, MIM, MBIM (nee Blight) (30 Oct 1921 - 4 June 1998) In the week in which she would have celebrted her 98th birthday, we remember Marion McQuillan, metallurgist who specialised in the engineering uses for titanium and its alloys. Born in Watford, Marion Katharine Blight came from a working class family, her father being a shop assistant and her mother working in domestic service. She was picked out early in her school days as exceptional and went to Wycombe High School and then Henrietta Barnett’s School on scholarships. In 1939 she went to Girton College, Cambridge, where she took a degree in natural sciences and metallurgy, enabling her to start as a Junior Scientific Officer in the corrosion section at the Royal Aircraft Establishment Farnborough (RAE) in 1942, with her new husband, Norman Petch, also a metallurgist, whom she had met at Cambridge. At the RAE she did research into metals for jet engines and was a member of the first team in Britain to carry out research on titanium. Despite her relatively junior status, she authored 5 reports at the RAE during 1944. Her marriage to Petch did not last and they divorced in about 1944 and in 1947 she married yet another metallurgist, Alan Dennis McQuillam. After a year at the Atomic Energy Research Establishment at Hartwell, where she worked on some of the early metallurgical problems of nuclear energy, Marion and Alan went to new jobs at the Australian RAE in Melbourne. On their return to the UK in 1951, she started what would be a career-long association with ICI Metals (also known as IMI), when she got a job as a technical officer in its Titanium Alloy Research Department. Two years later she had risen to become head of that section and in 1956 she and Alan published their seminal book “Titanium” which was subsequently also published in Russian. The 1960s were a very productive period for Marion’s work and professional standing. She registered 8 patents relating to titanium alloys. She rose to become the technical director of the New Metals Division of IMI in 1967 and in 1978 was appointed managing director of Enots, an IMI subsidiary, the first woman to become a managing director in the Imperial Metal Industries empire. Meanwhile she served on the Interservices Metallurgical Research Council (until 1989), was awarded the Rosenhain Medal in 1965 and elected vice-president of the Institute of Metals in 1967. The following year she was the guiding force behind the First International Conference on Titanium, organised by The Institute of Metals in 1968 in London. Although she could presumably have retired in 1981, and despite her husband’s death in 1987, she seems to have continued with aspects of her life’s work well into her final years. Marion died in 1998.  Engineer of the Week No.99: Maria del Pilar Careaga (26 October 1908 - 10 June 1993) On her 111th birthday we remember railway engineer and politician, Maria del Pilar Careaga. Maria del Pilar Careaga is considered to have been Spain’s first female industrial engineer, but she also went on to have a significant political career, using her position to advance women’s opportunities, including the first women in Bilbao’s police force. Born in Madrid, into an aristocratic family, she studied surveying and then completed her studies in industrial engineering at the Technical University of Madrid, becoming the first woman engineer in Spain, in 1929. In her final year she specialised in railway engineering and spent her practical internship as a train driver, becoming the first woman who drove a train in Spain, attracting a lot of media attention. However, she did not pursue an engineering career but was soon involved in politics, supporting Catholic women’s groups. During the Spanish Civil War she sided with the Franco supporters and was imprisoned until 1936. In 1943, she married Enrique Lequerica Erquiza, also an engineer. In 1958 the Pope granted her the Pro Ecclesia et Pontifice Cross "in recognition of the services rendered to the Church and to society”, the highest award open to women in the church and the first of many major awards and medals she received. In 1964 she became the first female elected as a provincial deputy (for Vizcaya County Council, and in 1969 she was elected to be Mayor of Bilbao, the first woman to hld a mayor's office during the Franco dictatorship. During her 6 years as mayor she oversaw many infrastructural and educational developments, but her alignment with the far right was becoming controversial and in 1979 she had the dubious honour of being the first woman to be shot by ETA (the Basque organisation Euskadi Ta Askatasuna). Although she survived a bullet in her lung, she retired from public life and died of liver complications in 1993.  Engineer of the Week No.98: Alice Jacqueline Perry BSc (Mrs Shaw) (24 October 1885-1 August 1969) On her 134th birthday we remember Alice Perry, the first woman in Europe to get a degree in engineering. In 1906 Alice Perry was the first woman In Europe to gain an engineering degree, the next women engineering graduates were not until 1912 (Nina Graham in England and Elisa Leonida-Zamfirescu in Romania). Alice was surrounded by the inspiring work of her father, a surveyor who founded a electric light company, and her uncle who invented the Perry navigational gyroscope, but it was her own outstanding talent for maths that propelled her towards her engineering degree from the Royal University, Galway. When her father sadly died just after her graduation she temporarily took on his role as County Surveyor for Galway but was not appointed to the permanent post. The work, for which she had assisted her father during her university vacations, entailed extensive travel from Clifden to Gort, inspecting roads and buildings. To this day, no other woman has ever been a County Surveyor in Ireland. From 1908-1920 she was a Lady Inspector for HM Factory Inspectorate, in London and Glasgow. She married Robert Shaw in 1916, but he was killed on the Western Front the following year. In 1921, as Mrs Shaw, she was promoted to Woman Deputy Superintendent Inspector in the Factory Inspectorate, but she retired from that work in the same year. She spent the rest of her career working for the Christian Science movement in Boston, writing poetry for the Christian Science Monitor and editing poetry for Christian Science journals. Today, Alice Perry is the inspiration behind the the Alice Perry Engineering Building at the National University of Ireland Galway.  Engineer of the Week No.97: Georgina Elizabeth Kermode (nee Fawns) MIM (1868 - 5th September 1923) Georgina Kermode, suffrage campaigner and engineer gave the lie to the old saying that beauty and brains do not mix. Georgina Kermode, although born in England, was from a 3rd generation Tasmanian family and married into the richest family in Tasmania. A very beautiful woman in an era when women of her class generally did nothing much but socialise, Georgina (also sometimes Georgiana or Georgine) was a suffragette, metallurgist, engineering entrepreneur and holder of numerous patents. She married landowner and ‘pastoralist’ Robert Crellin Kermode when she was only 17 and went to live in Mona Vale, a house so lavish it has 365 windows, 12 chimneys and 7 entrances, and is therefore nicknamed the “Calendar house”. 10 years later sees Georgina very active in the campaign for the women’s vote: running the Campbell Town Woman's Christian Temperance Union, despite the opposition of family and friends. As the Colonial Suffrage Superintendent of the WCTU, her aggressive propaganda initiative put pressure on politicians. She organised a 'winter campaign' in 1896, addressing well-attended drawing-room and public meetings all over Tasmania, gaining 2,278 signatures for a petition to parliament - a terrific result, given the small and isolated population. Perhaps this political activism was an education for her because another 10 years on and she is an engineer! Robert also had mining interests and somehow Georgina became sufficiently expert in the rich metal ores of Tasmania that she became a director of the Tasmanian Metals Extraction Co. Ltd., whose mines are still operating at Rosebery in the west of the island. There were technical difficulties in extracting the metals from the ores and she took an interest in this and travelled to England, probably in about 1904 to look into the possibilities of electrolytic extraction for the treatment of the zinc-lead ores. It seems that she never returned to Australia, although her husband probably visited her in the UK when he took up an army commission in 1914. From 1907 until she died, Georgina took out 27 patents (UK, USA, France, Switzerland and Denmark) for a variety of inventions. The principal focus for her during this period was automatic vending of postage stamps. She set up the British Stamp and Ticket Automatic Delivery Co. Ltd., whose machines were based on a design from NZ but with her various improvements which she patented, such as for detecting counterfeit coins. The Post Office started to buy the machines, with the very first being installed in the Houses of Parliament. The machines and the special rolls of stamps were known as ‘Kermodes’ but the system was taken in-house by the Post Office in 1920, Georgina was the first female member of the Institute of Metals, elected on 21 December 1916, the same year as she patented her design for ‘Improvements in Furnaces for Refining Metal’. Other inventions included a series of designs for a self-contained breathing apparatus, for divers and firefighters, very similar to Jacques Cousteau’s SCUBA of some 30 years later. There was a regenerative breathing-apparatus to chemically refresh exhaled air, a harness with mask, air bottles and valves and a selfcontained diving suit. Georgina and Robert had no children and she did not have good health in her later years although she was a regular attender at the Institute of Metals meetings and other mining-related organisations. She died in England but is buried in Tasmania.  Engineer of the Week No.96: Isabel Helen Hardwich (nee Cox), MA, CEng., MIEE1, MIOP, HonMWES (19th September 1919 – February 1987) Today we remember Isabel Cox, photometry expert and electrical engineer and WES activist. Isabel Cox, known to members of the Women’s Engineering Society by her married name of Hardwich, was born into modest circumstances in South London in 1919. She was educated at local council schools and then went to Newnham College, Cambridge where she gained a degree in physics. In 1941 she was one of the first batch of graduates to join Metropolitan Vickers’ ‘College apprenticeship’ schme in Manchester. This scheme was novel at the time, not only for taking women as well as men on an engineering apprenticeship but for its mix of practical work and explicit training for the graduates to become the firm’s future leaders. This included formal dinners for the apprentices, no doubt reported in The Rotor magazine which Isabel edited. Her first job after completing her apprenticeship was in their electron microscope division, then moved to the photometry laboratory. In 1945 she married colleague John Norman Hardwich, who was a man ahead of his time in his unswerving support for his wife’s work, even to the extent of joining WES and being involved in some committees. This enabled her to remain at work after they married at a time when this was still rare. In 1947 she joined the Illumination Engineering Society where she started her lifelong interest in educating the next generations of engineers. Metropolitan Vickers expected its staff to do external teaching, which Isabel did in various schools and colleges. In the 1950s Isabel set up a Hilger large UV spectrometer before she turned to X-ray crystallography and designed an X-ray Geieger counter spectrometer. She remained with MV, later AEI, responsible for the recruitment, training and general overseeing of their women engineers. She left AEI when it was taken over by GEC in 1969 and became Chief Clerk to the Open University in Manchester until she retired ten years later. Isabel joined the Society in 1941, became President in 1961-62 and was then very involved in setting up the International Conference of Women Engineers and Scientists (ICWES) as well as numerous other activities relating to encouraging young women to become engineers. She was made an Honorary Member of WES and after her death, her husband returned the complement by gifting the Society the beautiful silver WES badge to be the Isabel Hardwich Award, now our highest award, given for outstanding service to WES.  Engineer of the week No.95: The Hon. Lady Katharine Parsons (nee Bethell) JP (1859-16 October 1933) On the 86th anniversary of her death we remember Katharine, Lady Parsons, militant feminist and founder of the Women’s Engineering Society. Katharine Parsons was the originating founder of the Women’s Engineering Society. Described by Caroline Haslett as “a militant suffragette and feminist” it was Katharine Parsons who brought the women together who would, in 1919, become the founder members and signatories of the first articles of association to found the society. She, her daughter Rachel and her famous engineering husband, Sir Charles Parsons were lifelong supporters of the Society. Born in the East Riding of Yorkshire in 1859, she was the youngest of William Froggatt Bethell and Maria Elizabeth Beckett’s 12 children. Her father was a landowner and magistrate. It is most likely that all her education will have been at home as the first proper girls’ schools were only being established when she was a young adult. Like a later WES President, Lady Moir, Katharine Parsons was really an ‘engineer by marriage’. It is reported that as soon as she married Charles Parsons she started to take a detailed interest in his engineering works at Heaton. During the First World War she and her daughter, racel, were much involved in the recruitment, training and welfare of female munitions workers. In 1919 she became the first female member of the North East Coast Institution of Engineers and Shipbuilders and gave a rousing speech about women engineers at their victory celebration after the First World War. She also published a book: “Women’s work in engineering and shipbuilding during the war”. Her interest in women’s voting rights and their war work in engineering led to the idea for the Society which she partly funded from the start. She advertised for a General Secretary to help her set up and run the nascent society, and recruited Caroline Haslett. Together they established and ran the society in its early years and in 1922 Lady Parsons became its president. Although never formally trained or educated as an engineer, her contribution to engineering was widely recognised and she was also admitted to the Worshipful Company of Shipwrights and became a freewoman of the City of London. She died in 1933 and is buried in Kirkwhelpington, Northumberland.  Engineer of the Week No.94: Victoria Alexandrina Drummond MBE (14 October 1894 - 25 December 1978) In the week of her 125th birthday we remember Victoria Drummond, the first woman ship’s engineer and role model for women at sea, who were not able to follow in her wake until 10 years after she retired. Victoria Drummond, the first woman to become a ship’s engineer, may have come from the Scottish aristocracy but she had to work very hard in a very tough environment to become a chief engineer. Such privileges as being a goddaughter of Queen Victoria, were by no means sufficient to achieve what she did. Born in Errol in Scotland but also enjoying holidays in England with her grandmother who was an expert wood and ivory turner, Victoria was able to tinker with family cars and her family was able to help her first get an apprenticeship in a garage in Perth and then a full apprenticeship in the Caledon Shipyard in Dundee. By this time, her family had lost most of their wealth and she (and her siblings) had to make their own way in the world for the rest of her life. However, family connections did get her an introduction to one of the directors of the Blue Funnel Line, who was able to arrange for her to get her first sea-going job, as a very junior engineering officer. If this sounds as if she used privilege to get a job not normally available to women, any such privilege was of no further use: she had to show what a competent engineer she was to a very sceptical audience of traditionalist ships’ engineers. Some were supportive but many were openly hostile. Hostility was also embedded at the Board of Trade, who ran the examinations for all seagoing qualifications. The examiners passed her for her 2nd Engineer’s Certificate in 1927, but when she presented herself for her Chief Engineer’s Certificate they failed her more than 30 times as they could not stand the thought of a woman engineer in charge of an engineroom. Eventually she took the equivalent qualification in Panama, where the exam papers were anonymised. Most of her seagoing career was on non-UK ships, some 18 ships in total. In August 1940, she was serving on a Panamanian ship, the Bonita, in the North Atlantic when Luftwaffe aircraft attacked. As a neutral-flag ship, she was not protected by an Allied convoy. Drummond was on watch when near-miss bombs blew lagging off pipes in the engine room and split the main water service pipe feeding the boilers. She ordered her fireman and greaser to open the fuel injectors and main steam throttle to increase speed and then get out of the engine room in case they needed to abandon ship. The Bonita had never before gone any faster than 9 knots, but Drummond somehow increased speed to 12.5 knots which was enough for the captain to dodge the rest of the bombs dropped and make it to the USA in safety. Drummond was awarded the MBE and the Lloyds Medal for Bravery at Sea. She retired from the sea in 1962 and lived the rest of her life with her sister in London. She is commemorated by a Victoria Drummond Room at the IMarEST headquarters in London. A very detailed (if somewhat uncritical) biography, The Remarkable Life of Victoria Drummond – Marine Engineer, was written by her niece, Cherry Drummond, the late 16th Baroness Strange. Drummond was a very early member of the Women’s Engineering Society which published various updates on her career in The Woman Engineer.  Engineer of the Week No.93: Doris Mona Whiteside Hirst (Mrs Fairthorne) MA, AFRAeS (13th October 1903 – 16th February 1988) On her 116th birthday we remember aeronautical engineer, Mona Hirst. Mona Hirst was another one of the early female engineers who started out as a mathematician. From the modest background of a father who was a primary school teacher in Birmingham, she graduated from the University of Birmingham in 1924 with a Class 1 BA in mathematics. In 1925 she gained an MA in mathematics for her thesis on Asymptotic Expansions. Her next job was as a lecturer in mathematics at Queens University Belfast (QEB) where she worked from 1926-30, and co-authored a paper in 1928, in The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, on parallel-plate condensers. 1928 was apparently a ‘peak year’ for women’s papers in this physics journal until after the war, with QEB being exceptionally well-represented by women’s papers. She worked for a while as a Technical Assistant in the Aeronautical Department of Boulton & Paul Ltd, in Norwich, although it is not clear exactly when. The company was closely linked to the Royal Aircraft Establishment Farnborough (RAE) and the Royal Airship Factory Cardington for which they made all the R101’s structural metalwork in 1929, at the time when Hilda Lyon was doing the structural calculations for its transverse framing. She got a job at the RAE as a Junior Scientific Officer, probably in 1930, as in 1933 she wrote an article about wind tunnel work there, in The Woman Engineer. Unfortunately it is a general article and gives no indication of her own work there. In the same year she married RAE colleague Robert Fairthorne. It is not known if she resigned from her job on marriage, as would have been normal, or if she continued until her son was born in 1941, but she and her husband travelled to mathematics conferences at least until 1936. Mona died in 1988, still living in their house in Farnborough named Kirkmichael after the town of her birth in the Isle of Man.  Engineer of the Week No.92: Dina St Johnston (née Aldrina Nia Vaughan) (20th September 1930 - 1st July 2007) Today we remember Dina St Johnston, the founder of the UK’s first independent software house. Aldrina Nia Vaughan was born in south London in 1930 and educated at the Selhurst Grammar School for Girls. Although her parents wanted her to stay on and go to university she chose to leave school at 16 for a job with the British Non-Ferrous Metals Research Association. She studied part-time at Croydon Polytechnic andthen at Sir John Cass College, gaining an external London University degree in Mathematics. In 1953 she moved to Borehamwood Laboratories of Elliott Brothers (London) Ltd, where she worked in the Theory Division. It had a primitive computer called the Nicholas so she was sent on a short course in programming, at Cambridge, from which she quickly demonstrated a real flair. By 1954 she was responsible for the programming of the Elliott 153 Direction Finding (DF) digital computer for the Admiralty and soon after for programming Elliott’s own payroll computer. Her work was said to have been inventive and structured, but also very accurate, hardly ever requiring ‘de-bugging’. In 1958 she married the head of the computing department, Andrew St Johnston, and left Elliotts to set up her own software company, Vaughan, recognised at the time as the first such enterprise in the UK. Dina had recognised that as the pioneering computers moved out of the rarified science environments and into general business and industry, hardly anyone in the latter sectors had the skills or the time to develop the skills, to programme their new computers. She employed a few programmers, men with similar backgrounds to her own and her first contracts came via Elliotts, as they were among the first to produce computer hardware for business use. Very significant contracts came to her, such as programming early nuclear power stations, but in 1970 she branched out into hardware, producing her own computer, the 4M, and the company changed its name to Vaughan Systems and Programming in 1975 to reflect the new area of work. The company was growing fast and Dina was unusual for the time in taking on trainees with no prior experience. By the 1990s the company’s principal contract was for British Rail, ushering in a new era of real-time Train Describers which track train movements within a Signal box area and display the positions of trains on the main signalling panel, or on screens. In 1996 Vaughan Systems Ltd was sold to Harmon Industries, an American railway signalling company and, in 1999, Dina retired. The majority of this profile of Dina has been gleaned from an extensive obituary, by Simon Lavington (to whom I am indebted for bringing Dina’s amazing story to my attention), published in The Computer Journal (2009) 52 (3): 378-387, which includes a detailed list of her work.  Engineer of the Week No. 91: Minnie Elizabeth (Betty) Barclay Lindsay, BSc (9th October 1897- 11th January 1953) On her 124th birthday we remember Scotswoman Betty Lindsay, who despite her mechanical engineering degree worked mainly as a civil engineer in Albania. Elizabeth Lindsay was born in 1897 in China where her father, Edward John Lindsay was a banker. However, when she was only 3 years old the family returned to Scotland where her father soon died and she was sent to live with her grandparents near Elgin. When her mother, too, died in 1913, Elizabeth went to live with her uncle, Rev. Alex William Watt, at Evie in Orkney, which she regarded as her home address for the rest of her life. In 1921 she gained a BSc in mechanical engineering from the University of Edinburgh, and is believed to probably have been only the 2nd woman engineering graduate (after Elizabeth Georgeson in 1919). During her studies she was awarded a 2nd class certificate of merit in mechanical engineering. From 1922-25 she worked as a civil engineer, as an Engineering Assistant for William Tawse Ltd, on the Aberdeen waterworks Reconstruction scheme. Tawse were a major contracting company, who also built the Cruachan dam, and which later became the Aberdeen Construction Group. In 1926 The Woman Engineer reported: “Some time ago the WES was asked to find a woman engineer who would be prepared to join a Mission which was being organised by Lady Carnarvon to go to Albania in connection with an Anti-Malarial Mission. Miss E. Lindsay, one of our Scottish members, who has trained and worked as a Civil Engineer, volunteered for the post. The Mission consists of two women doctors, a nurse, a chauffeuse, and a woman engineer. Miss Lindsay arrived at the State Hospital, Valona, Albania, on March 21st, having stayed some time previously in Italy, receiving instruction in anti-malarial work. Her duties at present consist of organising and supervising the work of draining, ditching and filling in pits, etc., and in clipping for and examining mosquito larvae. She writes that the work is most interesting but progress is necessarily very slow.” From 1926 to the outbreak of war in 1939, Elizabeth worked on anti-malarial civil engineering projects in various parts of Albania, funded by various charities and the government. She worked for Rockefeller Foundation Engineer, Frederick W. Knipe, and International Health Board ecologist, Dr Lewis W. Hackett, who were the leading malariologists of their day. Whilst Knipe was the foremost proponent of chemical spraying to prevent mosquitoes, Hackett advocated environmental controls and Elizabeth’s work with him at Durazzo, involve increasing the salt content of a slough, in which mosquitoes were breeding prolifically, by connecting the slough with the Adriatic Sea, until the salinity was increased to a point which eliminated all breeding. In 1935 Elizabeth’s work would have involved her in the project which dammed the Tirana River in Albania to divert its entire summer flow into an irrigation system, with a view to preventing mosquito breeding during the malaria season. The Rockefeller Foundation’s annual reports do not name her, as she was not directly employed by them, but her role is described as “drainage engineer” working with Hackett. Much of the work was camping out in the field, surveying waterways, in what was then a very undeveloped nation. Conditions in the field would have been extremely basic and social attitudes towards women were probably very difficult. Nevertheless, she apparently thrived there, learnt the language fluently and made local friends. On her return to the UK at the outbreak of the Second World War, Elizabeth put these skills to good use and became a technical translator in both Spanish and Albanian, for the Air Ministry. Rising to the level of Chief Translator, she remained there until her death in 1953. She was buried in Edinkillie, Morayshire, where her grandmother added her memorial to the family grave.  Engineer of the week No.90: Dorothy Donaldson Buchanan (Mrs Fleming) (1899-1985) BSc, AMICE Dorothy Donaldson Buchanan, the first woman in Britain to gain qualification as a civil engineer, was born at Langholm, Dumfriesshire where her father, the Reverend James Donaldson Buchanan, was a clergyman. Perhaps because her upbringing was surrounded by the bridges and other local works of the great engineer Thomas Telford, Dorothy Buchanan’s earliest ambitions were to become a civil engineer. She was edducated at Langholm Academy, the Ministers’ Daughters College and Edinburgh University, she gained a BSc in Engineering in 1923. She studied under the Nobel Laureate Professor Barkla, but was delayed in graduating by illness. Another tutor, Professor Beare, recommended her to contractors, S. Pearson & Sons, but they would not take her until she had some experience. Fortunately, at just that time, (Sir) Ralph Freeman was recruiting staff for his work as consultant to Dorman Long’s on the Sydney Harbour Bridge. He appointed her to the design office at £4 a week- the same as the “boys”. She worked for a while “running out weights of members, panels, girders etc” but then sought work on the drawing office, to work on the southern approach spans to the bridge. Having gained the necessary experience, she was taken on by Pearsons in 1926 and worked on site at the Belfast Waterworks scheme in the Mourne Valley, where a reservoir was being built. This scheme ran into geological problems and the novel technique of using compressed air to dewater silty strata was used, giving Buchanan very interesting experience. Site work was apparently not a problem, with workers being content to see her as an engineer. She returned to Dorman Long’s drawing office to work on the George V bridge in Newcastle and the Lambeth Bridge in London as well as the Dessouk and Khartoum bridges in Sudan. In 1930 she left to get married (m. Fleming), feeling that to do both family and professional roles well would not be possible at the same time. Dorothy was an active member of the Women’s Engineering Society, to which she gave a paper on the designs of some of ‘her’ bridges, which was published in The Woman Engineer in 1929. She successfully sat the exams in 1927 to become the Institution of Civil Engineers’ first female chartered engineer (then known as associate membership), which she regarded as a highlight of her life. In later years she took up rock climbing and painting and she died in 1985. The Institution of Civil Engineers now has a room named in her honour.  Engineer of the Week No. 89 Judy Butland (née Whiteley) MPhil (6th October 1940 - January 2019) Today on what would have been her 79th birthday we remember Judy Butland, an engineering software designer who pioneered the use of computers at universities, her ‘Butland curves’ software still being in use. Born in Leeds, Judy’s lifelong struggle with severe arthritis interrupted her schooling but with a year at the local technical college she gained enough A-levels to start on a maths honours degree course at the University of Manchester. She found the lectures boring and did not complete her degree but in 1964 she married fellow student David Butland. Her first job was in the Information and Exchange section at AEI, Manchester, producing a weekly bulletin of technical articles and papers from engineering publications. In 1967 she was taken on at Manchester Business School as mathematical assistant to Dr Winifred Hackett, an aeronautical engineer. Hackett suggested that she might see whether computers would be useful for her research into the scheduling of the work flow in aeroplane production. The project entailed statistical analysis, which required complex calculations, so Hackett sent Judy to lectures on the principles of computing. The two women got along very well and this proved to be the start of Judy’s career in software engineering and she started to become computing advisor to other groups in the Business School, including a project with the Librarian to automate the classification of publications. Her next job was in the Postgraduate School of Electrical and Electronic Engineering at the University of Bradford (where her husband had also just found work), where they needed someone to supervise programming in research projects. University computing was at a very elementary level in those days and in many ways Judy did not immediately realise how innovative her work was. She developed a comprehensive set of tools to produce technical charts from research data, and made them freely available and it was soon being used in many universities. She wrote up the work she had been doing, and was awarded an M.Phil for her thesis. When she wrote an article about her work in an American electrical engineering publication, she had many requests for it from all over the world. The university soon realised that she was giving this software away so Judy set up a company to formalise the distribution, Bradford University Software Services (BUSS), and it was soon making enough money to take on staff, while she spent her time programming. She published a number of academic papers, including one on drawing a smooth curve though an arbitrary set of data points – a calculation that became known as Butland’s Algorithm. This is still in use today and a successor company, BUSS2, produces it as a smartphone app. Judy’s very severe arthritis inhibited her later years and her last paid work in computing was to develop an internet-based interface to control a robotic telescope on Oxenhope Moor. In her retirement, she and her husband kept chickens, were involved in the local Scouts and continued to travel until her arthritis prevented it. She died in 2019 and her family have produced a very detailed biography online ( https://jbrip.home.blog/ ) from which the majority of the information for this profile has been taken.  Engineer of the Week No.88: Dr Winifred Hackett AMIEE (2nd October 1906 - 3rd June 1994) On her 113th birthday we remember Winifred Hackett, electrical engineer. Educated at King Edward’s Girls’ High School, Birmingham, Hackett was an exceptional student and won a scholarship there. She initially went to UCL to study architecture but then returned to Birmingham to study electrical engineering, graduating with a BSc Hons class 1 in 1929 – the first woman to gain such a degree. This also gained her the Bowen Scholarship for Electrical Engineering enabling her to stay on for a year’s research for an MSc. In 1930 she was awarded a grant by the Institution of Electrical Engineers' War Thanksgiving Education and Research Fund which helped her proceed to gain a PhD on selenium cells from University of Birmingham. Her first job was as a Junior Technical Assistant to the British Electrical and Allied Industries Research Association at Perivale and then Leatherhead. Having been involved with the Women’s Engineering Society since 1929, in 1946 she became President. This was when she was researching dielectrics for “a firm of capacitor manufacturers”. She published a number of papers on dielectrics, capacitors and DC design. In the 1950s she was head of the Guided Weapons Division at English Electric, in Luton and later in Stevenage, where she was in charge of the Deuce computer and its programming on punched cards and paper tape. The Deuce was a version of Alan Turing’s Ace computer but was a commercial product, of which 33 were sold and which had a library of over 1,000 programs. The period when Hackett ran the guided weapons division also saw the development of the Thunderbird surface to air missile and other ballistic missiles. In the early 1960s she moved to join the Manchester Business School where she did statistical analysis. Personal interests included fashion and the theatre, and in retirement her own ill health led her to devise various aids for disabled people. She died in 1994. |

- Home

- Electric Dreams

- All Electric House, Bristol

- Top 100 Women

- Engineer of the Week

- The Women

- Timeline

- WES History

- EAW

- Teatowels For Sale

- 50 Women in Engineering

- Museum Trails

- Waterloo Bridge

- History Links

- Blue Plaques

- Virtual Blue Plaques

- Career and Inspiration Links

- Contact

- Outreach

- Photo Gallery

- Bluestockings and Ladders